In a recent short film, starlings help a lonely elderly man find his way back to the experience of the world around.

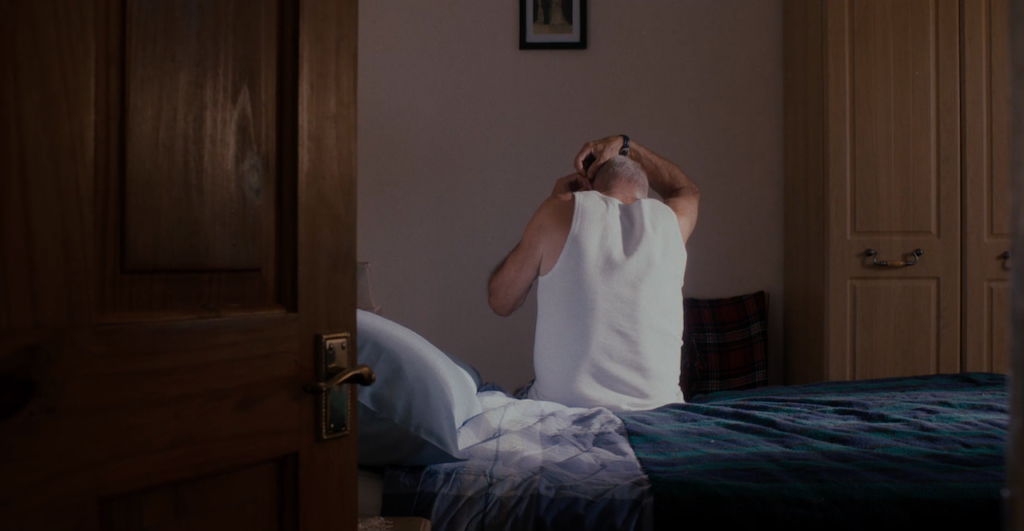

It is silence that opens the short film Starlings, directed by Simon Allen. But despite the dullness of muffled noises suffocated in the background, it speaks loudly, in a captivating fashion. And it does, for the protagonist of this story has to respond to two types of deafness.

The first is a physical impairment that requires him to wear a hearing aid to retrieve his ability to detect sounds, while the second is a form of social isolation, perhaps fed by the awareness that the device allows him to get back, which keeps him out of a world that he does not feel connected to anymore.

“I wanted to explore the concept of loneliness,” said Alexandra Prew, who wrote the script of the film. “I was really interested in a silent film with no dialogues, which I knew was going to be a challenge.”

The picture, presented in-person for the first time at the London Short Film Festival last January, was selected along with six other international submissions as part of Anthropocene’s Deities. The event, held at the Institute of Contemporary Art, aimed at digging into and contemplating the richness and fragility of ecosystems, where several, divergent beings run into the other and interact.

The single human character, played by Bedfordshire actor Carl Welch, is an elderly man whose name remains unknown almost to avoid any specification that could limit the narrative to only one person. He spends the days growing plants in his garden and, as if these were mirrors of his solitary existence, shielding them from the attacks of starlings that land on the allotment and eat produce.

“The movie captures the loneliness of capitalist societies in our disconnection from nature,” said Emma Bouraba, who curated the programme and took part in the pre-selection of films to be later shortlisted for this year’s edition of the Festival. “It shows the fight we have against the ecology we are a part of.”

Starlings turn out to be the ultimate species to convey this message. They act as intruders that invade and hinder the cynical, self-centred and isolated life cycle of the man and his vines, which reject any experience of concurrence and seek their expulsion.

“I got googling starlings and I was like, wait, everyone hates these birds,” said Prew. “They are huge pests: a big problem for agriculture and farming.”

According to research, European starlings are often the reason of damages to apples, blue berries, cherries, figs and grapes, as they either cause direct losses from eating fruits or reduce product quality by pecking and slashing at them.

The ecology portrayed in the film is analogous. Human conventions are unearthed and relentlessly confronted with the perseverance of the birds that, despite the manifold attempts set out by the man to send them away, carry on returning.

An anti-bird netting, stifling and tightening around the plants, as if to put an end to the growth that would bring them into a direct discovery of their surroundings; ultrasonic repellents to annoy the birds and even the classic scarecrow, made from scraps, cuttings, leftover buttons, that the protagonist tries and make abnormal and intimidating in accordance with human perception, which is accustomed to creating and loathing what is Other. All efforts would fail in their intent.

The dread of the unnaturalness would only be conceived by the man and rather overlooked by the still innocent, uncorrupted birds. Nonetheless, the solution would be meanly found by killing one of them, ultimately eliminating what is seen as unwelcome and further isolating from the experience of social contact.

Shot during the second wave of harder restrictions imposed in the U.K. to quell the spread of the coronavirus, the short film was able to touch on the question of loneliness as people were increasingly becoming familiar with it.

“I wrote the script before lockdown happened and before we even knew anything about Covid-19,” said Prew. “Then the subject matter became even more prevalent.”

According to a survey published by the Office for National Statistics in 2020, the equivalent of 7.4 million people said that their well-being was affected through feeling lonely during the first month of lockdown. In particular, research found that those aged 16 to 24 were more likely to have experienced loneliness due to Covid-19 tough regulations, namely 50.8% of respondents.

A previous report that had looked into the impact of loneliness in similar age groups in 2017, published by U.K. charity Action for Children and the MP Jo Cox Commission on Loneliness, had found that 43% of young people had undergone through such feelings even prior to the pandemic.

The actual number of teenagers and young adults suffering from this condition might even be higher, as loneliness often trivially conceals among people who experience it despite the fact they are not necessarily alone.

“Loneliness is a subjective feeling that arises when one feels that there is a gap between their desired and actual social contacts,” said Sam Fardghassemi, who is teaching fellow in the Department of Clinical, Educational and Health Psychology at UCL and has conducted in-depth work to analyse the issue in young people of London.

Due to this ambivalence, loneliness differs from social isolation. This circumstance, in which the man is presented in the first half of the film, can be described as the objective, partial reduction or total exclusion of other social contacts from one person’s daily life.

Japan has often been associated with the issue. In the country, young adults who are socially reclused are estimated to have topped 500,000 and different nuances of withdrawal have been found over time.

Sotokomori (Japanese for withdrawn, outside) refers to people whose outings are only limited to pursuing their interests, their agenda, or fulfilling practical needs such as food shopping. A more acute type of isolation concerns hikikomori (Japanese for withdrawn, inside), who are known to totally cut themselves off from the external world.

The latter state is emphasised in the man’s purchase of ultrasonic repellents to try and get rid of the birds, that he makes online, without leaving home and confining in a comfort zone he has built, whereby nothing else can meddle.

“It is as if they continue to exist as a being while being socially dead, and passively observing outside activities,” said Dr Maki Rooksby of the Institute of Psychology and Neuroscience at the University of Glasgow, whose expertise also covers social isolation.

Discovered in the mid-1980s as a socio-cultural phenomenon by Japanese psychiatrist Tamaki Saito, who would later coin the term, hikikomori only seemed to belong to Japan.

“I had not come across anything the same as hikikomori, as a recognised, semi-widespread, identifiable social phenomenon in the UK,” said Professor Robert MacDonald, who is co-Editor in Chief of Journal of Youth Studies, referring to a piece he had written in 2015 about the existence of British hikikomori.

More recently, things might have changed.

“Although we don’t know very much whether some countries are more vulnerable to it and how, we know it is a global mental health issue today, with cases reported throughout the world,” said Dr Rooksby.

Identifying, gauging and understanding the issue allows us to figure out the most appropriate solutions to let patients get back to appreciating the beauty of discovery and contact with what is around.

“Effective treatment approaches include those where clinicians tune in with the withdrawn person and share the journey of exploring interests or activities that may help them find meaning in their lives,” said Dr Rooksby.

In the case of the protagonist, the journey will be the pictorial flight of starlings shown in a documentary on television, where the birds dance and shape cinematic images in the sky in a rigorous-yet-liberating synchronised hymn to community and interaction.

The murmuration will work as a glimpse of the world that he has missed and still might miss; a glimpse of the complex system of our contemporary societies in which the role of each component is critical but always dependant on the acknowledgement of the Other.

It will work as a positive change of the man’s mind, a mighty driving force that will get him out of his armchair, out of his house to buy food dispensers that would feed those birds that, he now knows, are worth welcoming.

*

Starlings is available for free on Vimeo.