By Sarah Angel Majeed

In the liberal West, videos where people proudly discuss their sexuality and pronouns are commonplace. However, in Nigeria, being part of the LGBTQ community is illegal,– and if an individual is found to be in a gay marriage or having gay sex, they are sent to prison. However, aside from the legal repercussions, gay and non-binary people can face cultural abuse, harassment and shunning from their families and communities.

On 24th January 2023, Nigerian police said they would be investigating a video posted to X (formerly Twitter). The video features six Nigerians who are proudly stating they are lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender or non-binary.

Olumuyiwa Adejob, the Nigerian police force spokesperson, told X,

“[The people in this video] are criminal and punishable under the law. We are on this clip to take necessary action according to the provisions of the law in Nigeria. These are unnatural offences and are totally condemned.”

The Astrea Foundation, an organisation that specialises in advancing LGBTQI rights worldwide, was behind the video published to X. In a statement, they said, “We stand with our employees and partners in Nigeria in their uncompromising fight for the furthering of LGBTQ human rights.”

The video and Adejob’s comments received mixed responses on X. @Ayoksy wrote underneath the video, “It’s a crime to encourage the lifestyle. Read your laws!”. While @Empress_Viki commented on Adejob’s statement, “Please explain what is unlawful in that video according to the law of the country. It’s a video and what people choose to do with their body.”

The original video resonated with many West Africans, those who live in West Africa and those who don’t. “Mixed reactions like these aren’t uncommon,” says Nkara Ujah, a 24-year-old dancer born in Oyo, Nigeria, who now lives in London. “When I came out to my family as non-binary, my father didn’t even believe me, thinking it was a phase and I was straying from the path of Christ.”

Doctor Louise Chambers, a transgender professor in cultural studies and psychology at Goldsmiths, explains what these classifications mean. “There is a difference between trans and non-binary is that trans people identify with the opposite gender to their birth,” she says. “Non-binary people don’t identify with either gender. Yet the two communities both fall under the term ‘trans’ because they don’t identify with their birth gender.”

“It wasn’t until I came to London, where I took part in Trans pride, that I felt seen and was able to meet fellow trans and non-binary individuals,” says Nkara.

While anti-trans viewpoints are still commonplace in Nigeria, there has been progress in trans visibility. On 18th January 2024, Chizelu Emejulu, a Nigerian human rights lawyer, represented his client Abeni*, who testified in Lagos court about a man who lured her using a dating app to then beat and rob her. Abeni was open about being a transgender woman on the stand and was recognised as a woman by the Nigerian court.

“Abeni was treated with respect and didn’t have her transness used against her by the judge and the police,” says Emejulu, who went on to note that this was significant progress for Nigerian LGBTQ rights. “This case making it to court and the suspect being charged is historic as traditionally LGBTQ victims are ignored by the police,” he says.

While this is a huge step forward, more progress needs to be made to improve the safety of trans and non-binary people. “Victims are too scared to speak out, and lawyers like me can rarely assure them coming forward is worthwhile,” says Emejulu.

Emejulu is currently challenging the provisions of the Same-Sex Marriage Prohibition Act (SSMPA) at the Federal High Court, Lagos. These sections he is challenging prohibit entering a same-sex marriage, which is punishable by 14 years in prison. The law was passed in 2014, but anti-LGBTQ attitudes have been around far longer.

“I came out to my family in 2014 and was met with nothing but hostility,” says Ellis Aku, a non-binary 26-year-old writer, a second-generation migrant. “Our relationship completely crumbled, we went no contact, and we have only now, 10 years later, been working towards mending our relationship. Even after all this time, they still misgender me.”

“I was considered a disgrace, bringing dishonour to the family,” says Ellis. “I was very grateful to be in London because I could find people to help me, whereas back in Nigeria, I would have lived in fear of anyone finding out about my identity.”

Ellis’ fears are not unfounded. In 2014, when the SSMPA was passed, four men were publicly whipped in Northern Nigeria for being convicted of engaging in gay sex. In Bauchi, Nigeria, three men were sentenced to be stoned to death for engaging in gay sex.

Public shaming like this are not uncommon, and the anti-LGBTQ mindset exists in all spaces in Nigeria. Speaking on the rise of LGBTQ visibility, Professor Haroun Isah, Professor of Medicine at the University of Lagos, said, “The West is promoting LGBT and seeking to railroad African countries into accepting this ‘norms of theirs’. While African countries’ norms and morals should be respected by the West.”

“Many Nigerians are raised in conservative Christian households, and these values should be respected,” says Professor Isah.

But Ellis disagrees, “Despite the conservative Christian nature in Nigeria, things have been changing,” says Ellis. “Second-generation people from London are now going back to West Africa to showcase us and create a community for queer people.”

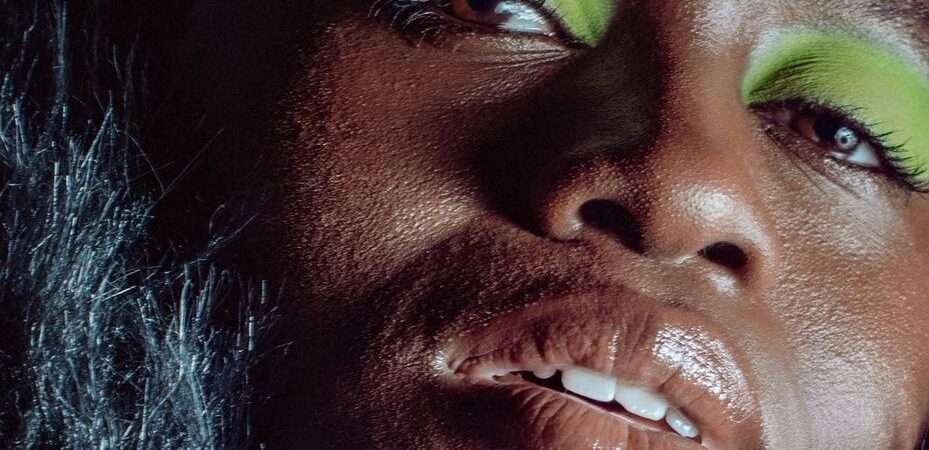

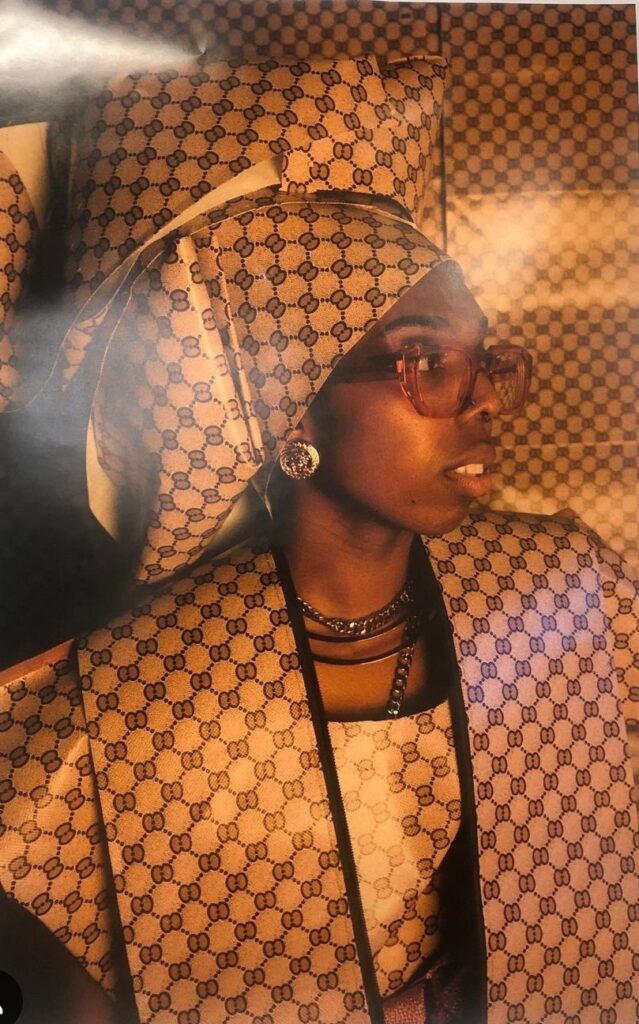

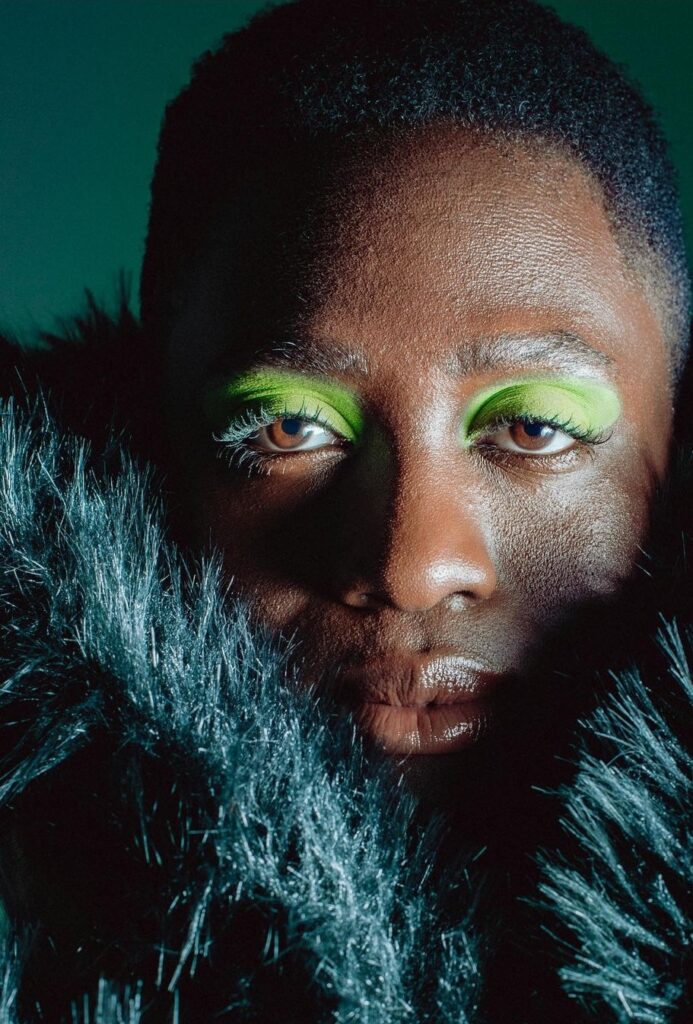

Nii Nai is a non-binary creative director who has taken their knowledge from the London Ballroom community and is bringing it to West Africa with Open Ballroom sessions. “London Ballroom is all about the queer community and loving yourself through vogue, fashion and makeup,” says Nii Nai.

The Open Ballroom sessions currently occur in secret locations, jumping back and forth between Ghana and Nigeria. “We keep the location discreet to protect our member’s safety,” says Nii Nai. Safety is more important than ever as Ghana, on 28th February 2024, passed a bill which makes it illegal to identify as LGBTQI; anyone who is charged will serve five years in prison.

“Since our start in December, we have multiplied in numbers, and we have been able to bring so many queer West Africans together.”

Outside of the Open Ballroom sessions, there is also Lagos Pride and The Queer African Network. “Currently, we work online to bring Queer Africans together. Our goal is to create a community for all queer Africans so they feel safe, supported and know that they are not alone,” says Nii Nai. “We have seen a consistent growth in numbers as more trans and non-binary Africans are in the limelight.”

The rise of visibility for non-binary West Africans has led to a changing ideology, as Nkara has experienced. “I was fortunate that despite my father’s doubts, my mother was extremely supportive of me and my identity,” says Nkara. “She has gone beyond supporting just me to being an ally and activist, signing petitions against the SSMPA and informing her friends about being an ally.”

“With increased visibility comes more understanding and acceptance from those not in the community… I am proud to be Non-Binary and Nigerian.”