“What do you think the statue would say if it could talk?” filmmaker and history enthusiast David Peter Fox, 59, asked his children Leah and Alfred as they strolled across King’s Garden in Copenhagen.

They were admiring fable writer Hans Christian Andersen’s statue, which would become the first of many sculptures David brought back to life.

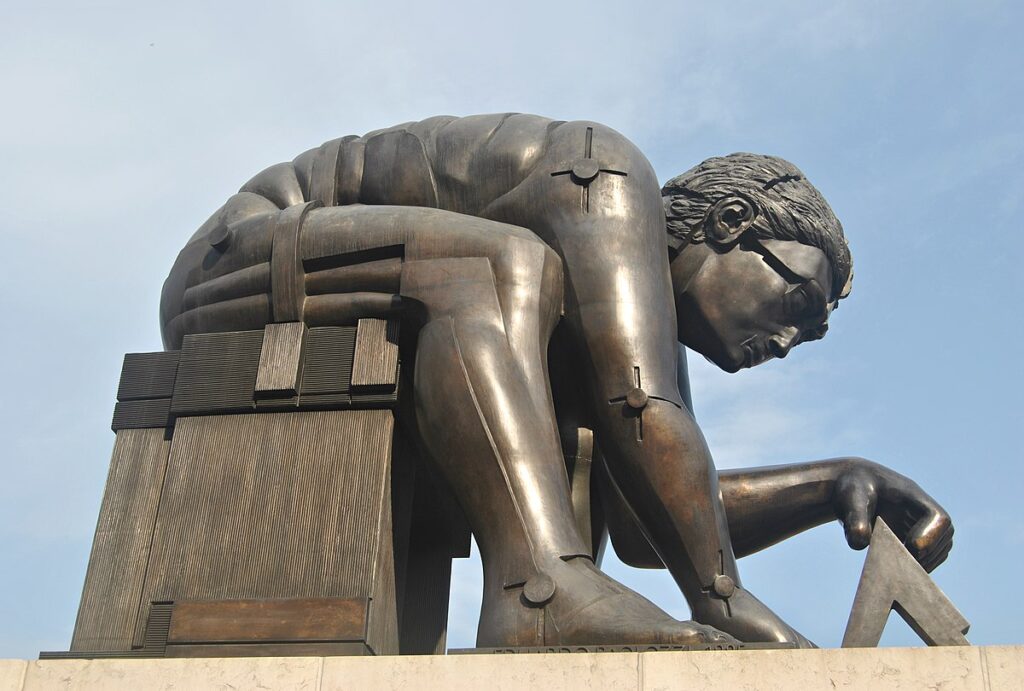

Talking Statues was launched by David in the Danish capital in 2013 and has now spread to over 20 cities across the world, including London. The cultural project consists of public statues placed in central locations recounting their stories thanks to a recording of a monologue, which people passing by can access through a QR code or an app simulating a phone call from the statue itself.

While David wrote the very first speech for H. C. Andersen, Talking Statues now hires scriptwriters to develop their monologues.

Rayandbee

“What is interesting about statues is that they represent a city,” says David. “The statues give the community a sense of pride.”

After researching the most interesting statues in each city and having gained permission from the municipality, the team behind Talking Statues scripts a short monologue of around three minutes and then finds a performer to record it.

“We look at the statue and then we try to find a voice that matches, the idea is to make the illusion work,” explains David.

“The statues give the community a sense of pride”

Throughout the years, the project has involved big names in the entertainment industry, such as Viola Davis and Meryl Streep, who voiced two of the characters in the Women’s Rights Pioneers Monument, in the middle of New York’s Central Park, or Jeremy Paxman, who is the voice behind John Wilkes’ statue in Fetter Lane.

“I have been making documentaries and television during the first part of my adult life; I have always learnt to look for stories,” says David.

The statues talk about themselves as if they are ghosts. They can travel through time and look at their past lives, their present as statues and, at times, even reflect on their own death.

David and his team contemplated making the statues more interactive by allowing them to be a bit rude towards the onlookers.

For example, Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard, known for his demeaning nature was a bit of a challenge for Talking Statues back in 2013. He was always against people taking pictures of him during his life, so the team initially made the philosopher’s statues in Copenhagen tell people off for taking pictures.

They soon realised however that a more polite approach – backed by interesting information – was much more appealing. “You want to entertain people but also enlighten them,” says David.

Talking Statues doesn’t shy away from controversial sculptures either. Explorer Christopher Columbus’ statue in Central Park was under scrupulous debate for his violent interactions with Native Americans.

“It was only through the perseverance of a new writer that the narrative was reshaped into one that resonated with the public,” says David. “The revised depiction, crafted with care and sensitivity, managed to navigate the stormy seas and write a good monologue everyone was happy with.”

On the other side of the world, Talking Statues gave a voice to 20 iconic personalities in British history, such as Queen Victoria, Sherlock Holmes, Isaac Newton, and George Orwell.

Not only that, it also made sculptures of animals speak, among which are Hodge the Cat in Gough Square and I Goat in Old Spitalfields Market.

A report by the Research Centre for Museums and Galleries found that Talking Statues received a lot of traction when it first came to London in 2014, attracting over 20,000 scans of the QR codes, with users describing their experience as “wonderful, interesting, brilliant, enjoyable and informative”.

The concept behind the project has predecessors that trace back to Ancient Egypt.

In his paper, “Talking Statues: What can and can’t be said”, David explains how Egyptians used to build statues of gods to be worshipped. The aim was to give the illusion that the oracles were alive and could talk to people, which was done by using a rubber hose pipe inside the statues through which priests would secretly talk.

He adds that the idea of talking statues with this exact name was taken on by Roman citizens in the 1500s but with a completely different purpose. Statues would “act as a place for public dialogue”. In fact, people could leave notes onto sculptures criticising and satirising the pope and other public figures.

“You want to entertain people but also enlighten them”

Only with digital development could Talking Statues happen as we know it today. While advancement in technology allowed the project to exist in the first place, the advent of AI is making the whole process much easier, doing background research on the history behind the statues.

For now, AI’s assistance remains behind the scenes, but David hopes that, in a few years, AI will allow Talking Statues to be even more realistic by letting people not only hear the sculptures’ stories but also to have real-life conversations with them.

So, if you are wandering around the streets of the Big Smoke and are in desperate need of a chat, pay a visit to Queen Victoria at Blackfriars Bridge because she’ll have a lot to say.

Find more information about Talking Statues in London here.

Explore more

-

Passion on and off the pitch: The struggle to watch football

-

The Old Operating Theatre: A walk through preserved lungs and hanging skeletons

-

Pitchblack Playback: An immersive deep listening music experience

-

Latex and leather: Inside London’s sex parties

-

What is ‘going boy sober’ and why is it trending on TikTok?