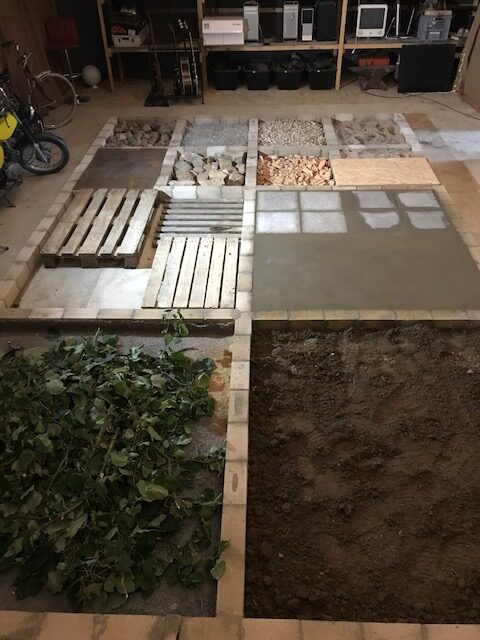

A large silver screen is showing Mission: Impossible in a dark soundproof room for the 50th time of the day. But there are no red velvet chairs. Instead, there is a row of square-meter surfaces. Wood, sand, cobblestones, dry straw on soil; a couple of different floor types are aligned next to each other and a few more are leaning up against the wall. As Tom Cruise leaps from one rooftop to another and crashes motorbikes, foley artist Pete Burgis points a microphone towards his feet, throws himself on the concrete surfaces and slaps them with his hands. His movements look nothing like Tom Cruise’s stunts. But they sound exactly like them.

Foley is the art of recreating everyday sounds for films in post-production. Named after Jack Foley, the stuntman for silent films who developed the practice, Foley is the performance of an artist who mimics on-screen actions and movements to make films sound the way life sounds. It is based on the idea that people hear what they are conditioned to hear – rather than what they are actually hearing. In other words, it is based on the idea that crackling bacon often sounds more like rain than rain itself.

Foley artists recreate absolutely everything, from clinking spoons stirring tea in a porcelain cup to sloppy kisses. For Pete, one of the UK’s most established foley artists and winner of two Primetime Emmy Awards, Foley “helps suspend disbelief”. He says: “The audience can’t feel or hear the atmosphere in a forest scene because the forest is actually in a studio. The whole point of my job is to help them believe what they are looking at is real.”

To create that layer of reality and immersive experience, foley artists break up the recording process into three parts, before sending the soundtracks to a foley editor who will sync them to picture: footsteps, props and move tracks. For the same one-minute-long scene, the Foley could be broken up into hundreds of tracks. For the audience, it’s one cohesive battle scene; for a foley artist, it’s hundreds of separate tracks of clinking chainmail, swishing swords, splattering blood – each character has their own sounds.

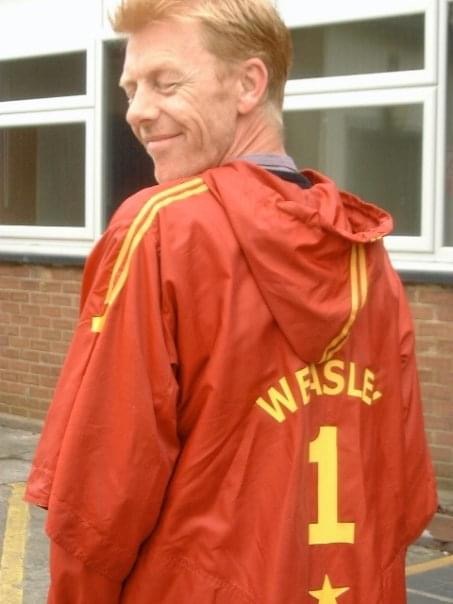

“I’m not here to make my own noise. As an artist, I am here to create someone else’s noise”

Pete Burgis

Footsteps are the most common sound in Foley. From Marie-Antoinette’s Rococo heels on Versaille’s marble floor to a hurried businessman’s Oxford shoes on concrete, every single step has to be recreated. For foley artist and supervisor Barnaby Smyth, footsteps are the hardest thing to master: “I am trying to convince the ear of the audience that I’m walking forward, even though I’m walking on the spot on my square-metre surface. I hit the heel first and then roll my foot so it doesn’t sound flappy and static.”

Barnaby stores hundreds of different shoes on a massive bookshelf he inherited from his grandparents. In between high heels, army boots and slippers, he has his “Gary Oldman shoes” that he wore when he did Gary Oldman’s steps on Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy, alongside the ones he wore when he was Diego Maradona on the football pitch in the eponymous documentary. His shoe collection mainly comes from eBay, car boot sales and charity shops, and it never stops growing: “There’s a charity shop down the road from our Essex studio, so every time I go past it to get lunch, I nip in and see if they’ve got any new shoes to update the collection and the range of sounds we can create.”

Footstep mastery is one you learn from experience and observation. “I’m not representing myself, I am translating things I have picked up and remembered,” Pete says. He used to sit on Brighton’s seafront to watch people walk and “mimic all the different gaits and footsteps while sitting down,” he says. “I realised there is so much character in footsteps.”

The true creative performance of Foley comes with props tracks. Picking a glass up, sitting on a creaky chair, firing a gun – foley artists come up with ideas, manipulate props, and reinvent any sound that is on screen. Celery is the go-to for breaking bones, over-boiled pasta forms a coagulant goo that is perfect for squishy guts, and melon pulp is for skin being peeled off. For one of the first foley projects in his career, the 1998 vampire film Razor Blade Smile, Pete remembers going through entire bags of vegetables: “Vampires don’t eat; they puncture and suck. So I used ripe pears, as the skin remains quite firm, and I could still bite into them and get a cracking sound. Then, all the juice dribbled down my chin as I got my teeth into it and sucked it.”

“Many things in the world make similar noises, you just have to find the right props to recreate a specific sound”

Barnaby Smyth

Fruits and vegetables are mainly used for human body sounds. For the most part, foley artists use a wide range of props to recreate sounds. Barnaby’s 2000-square-foot warehouse studio is a one-stop shop. Any object can be found – or recreated. “It’s very rare that an object sounds like itself. Many things in the world make similar noises, you just have to find the right props to recreate a specific sound,” he says. Among thousands of objects are real weapons – machine guns, pistols, axes, swords – alongside car parts, stationery… Plus many drawers filled with medical gear, animal accessories, police equipment or even Edwardian tea cups used in Downton Abbey. All quite bulky compared to sex scenes, where all Barnaby needs to do is slap his arm and kiss the back of his hand.

As a performance art, Foley is very similar to acting. “I’m not here to make my own noise. As an artist, I am here to create someone else’s noise,” says Pete. This is particularly the case when they record movement tracks, mainly recreating the sounds the actor’s clothes make. Foley artists rarely wear the clothes they are dubbing, but they perform in a way that creates the exact sound the audience expects to hear. Pete’s approach to this process is close to acting: “I create sounds in a linear fashion, character per character. I pick up an actor’s energy and decide I am going to be them for the day, recreating each one of their noises,” he says. “I can’t be Tom Cruise and an old woman crossing the street the next second. If I’m going to be Tom, I’ll lock Tom’s energy in my head for the day.”

Pete used the same dedication to getting into character throughout the entire Harry Potter franchise, which he worked on for a decade. “When we did the final battle sequence, every element of those ten years of work had to come back together, I had to remember how to be everyone. It was a very emotional moment knowing it was the last time I was going to be Harry Potter,” Pete says. “I had to re-do the scene where Harry walks down the Hogwarts staircase so many times because when I got to the bottom of the stairs I was always in tears,” he says. For Harry Potter, just as for Steven Spielberg and Tom Hank’s Band of Brothers, Pete used the original set costumes for movement tracks, for a more authentic and elaborate soundscape. “We were in the studio wearing real American uniforms and boots from World War 2,” Pete recalls.

The acting side of Foley is even more tangible when artists record on location rather than in the studio. If it often doesn’t make for the best-quality Foley, it does add a noticeable layer of authenticity. For the war drama Darkest Hour, Barnaby got access to the historical war rooms in London. “I sat in Winston Churchill’s famous chair in the cabinet room to create the exact creaking sounds we needed,” he says. “And there is a part where he taps his ring on the chair. That was my wedding ring. On Winston Churchill’s chair. [director] Joe Wright and the entire team were so excited by this added layer of reality.”

To mimic and recreate actors’ performances exactly as they need them to sound like, foley artists work to master as many skills as possible. Chacha, ballroom dance, waltz; Pete even took tap dance classes to dub Hugh Grant’s feet in the Paddington 2 dance scene. “My body is used to physically performing things like locomotive sounds, which is a different muscle memory to the one I use when walking down the road,” Pete says. “That’s the artistry.”