A £5 dress, worn twice, then discarded. A factory worker sewing for 75 hours a week. A landfill, overflowing with last season’s trends. Fast fashion moves quickly, but its effects last.

In the early 2000s, brands like Zara and H&M revolutionised fashion by accelerating production cycles. But in 2023, Shein took it a step further, releasing up to 10,000 new designs per day — something even traditional fast fashion brands never imagined. Welcome to the era of ultra-fast fashion.

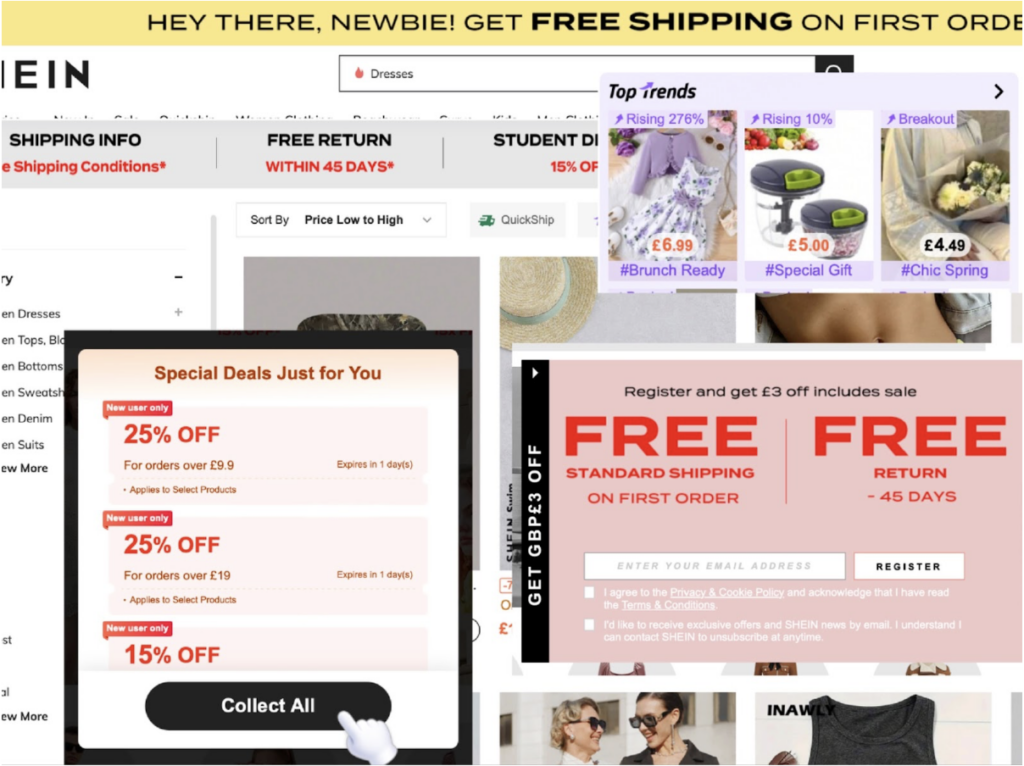

Shein’s success is driven by affordability, rapid production, and social media influence. The brand relies on social media-driven shopping habits, where trends rise and fade within weeks. Although Gen Z is seen as the most sustainability-conscious generation, it remains one of Shein’s largest customer groups.

For Gen Z, shopping isn’t just about necessity — it’s entertainment. Scrolling through Shein’s app mimics the fast-paced, reward-driven design of TikTok, turning shopping into a dopamine-fuelled habit. A ‘£3 top’ feels like a low-risk decision, but multiplied across micro-trends, it fuels overconsumption without Gen Z fully realising the impact.

Shein hauls aren’t just shopping — they’re viral content, designed for likes and engagement. On TikTok, #SheinHaul videos rack up millions of views, with influencers showcasing bags of clothes for the price of a single high-street outfit, further fueling trend-chasing and overconsumption. Beneath the ultra-low prices is a cost rarely seen.

How overconsumption turns clothing into landfill waste

Fast fashion doesn’t just expand wardrobes — it creates landfills. The industry produces 92 million tonnes of textile waste every year, with many garments discarded after only a few wears. And Shein, with its ultra-low prices and endless stream of new arrivals, is driving a culture of disposable fashion.

Most discarded garments end up far from where they were purchased. In Accra, Ghana, bales of secondhand clothing — often fast fashion returns or unsold stock — flood local markets. Unsold clothes pile up in landfills or clog waterways, contributing to severe pollution.

In Chile’s Atacama Desert, an estimated 39,000 tonnes of unsold fast fashion clothing have been dumped, forming vast textile waste sites. Many of these garments are made from synthetic materials like polyester, which take centuries to break down.

Sustainability or greenwashing

In 2022, Shein launched Shein Exchange, a resale platform aimed at promoting secondhand fashion. While this seems like a step towards sustainability, the sheer volume of production means that resale alone cannot counteract the industry’s waste problem.

Some brands are shifting towards circular fashion models, investing in garment recycling programs and designing longer-lasting clothes. Patagonia encourages customers to repair rather than replace. In France, a new law bans fashion brands from destroying unsold clothing, forcing companies to rethink waste management.

Without systemic regulation and meaningful shifts in consumer behaviour, fast fashion’s overproduction cycle will continue unchecked. But Shein’s environmental toll isn’t the only cost — it’s also built on exploitative labour conditions.

The human cost of producing ultra-cheap, disposable fashion

As landfills overflow with discarded Shein garments, the reality of their production tells a different story — one of long hours, low wages, and hidden supply chains.

A 2022 BBC investigation uncovered severe labour law violations in Shein’s supplier factories, where some workers were reportedly sewing for up to 17 hours a day, earning as little as £1 per hour. Employees described severe exhaustion, pay deductions for mistakes, and intense pressure to meet high quotas.

Despite Shein’s pledges to reform, reports continue to reveal excessive working hours and low wages in its factories. Without independent audits and greater transparency, critics argue that true accountability remains elusive. A 2024 Public Eye report reinforced these concerns, uncovering persistent labour violations despite Shein’s claims of improvement.

Lack of transparency in Shein’s supply chain

Shein has grown into a global leader in fast fashion, yet its supply chain remains largely hidden. Unlike brands such as H&M or Zara, which disclose their factory lists, Shein does not publicly share details of its third-party manufacturers. According to a report by The Atlantic, this opacity makes it difficult to assess working conditions, wages, and compliance with safety regulations.

In response to growing criticism, Shein announced a $15 million investment in 2022 to improve conditions across its supplier factories, promising better monitoring and upgraded facilities. Yet, despite these claims, investigative reports continue to expose child labour and illegal working hours in Shein’s factories, raising doubts about whether these reforms are truly effective. Some governments are cracking down, but Gen Z — the very generation that made Shein a global giant — cannot demand change while continuing to fuel the problem. While resale platforms like Depop are gaining traction as sustainable alternatives, they remain a niche solution. Shein hauls continue to dominate online spaces, reinforcing an addiction to overconsumption. Until Gen Z confronts its role in keeping ultra-fast fashion alive, true accountability will remain out of reach.