They once fought for Hong Kong’s freedom, but now, they fight to keep their voices alive in exile.

Three young women — Anna Kwok, Chloe Cheung, and Kacy (a pseudonym), once stood side by side in the streets of Hong Kong, fighting for democracy. Now, they’ve been scattered across the world, their struggle continuing in exile.

They each navigate exile differently: Anna lobbies in Washington, Chloe questions what activism means for her future, and Kacy, now in the UK, feels caught between two worlds. Regardless of their different paths, one undeniable truth remains: they can never return home.

Anna Kwok: From filmmaker dreams to global advocacy

At 23, Anna boarded a plane, believing she’d return to Hong Kong in a few months. Five years later, she’s now on Hong Kong’s most-wanted list. Her activism began in 2019 during the pro-democracy protests, a movement that has since altered the course of her life.

She played a key role in organising a global campaign at the G20 summit, publishing advertisements in 16 newspapers across 13 countries, urging world leaders to “Stand with Hong Kong.”

In 2020, after the national security law was imposed, she faced a stark choice: return and risk imprisonment or continue advocating from abroad, and in the end, she chose exile. Due to her decision to work in the public eye, consequences soon followed. In 2023, she was placed on the Hong Kong police’s “wanted persons” list, with a HK$1 million (equal to £100000) bounty on her head. “I don’t know if I’ll ever see Hong Kong again,” she admits. “But even if I never return, I will always be a Hongkonger.”

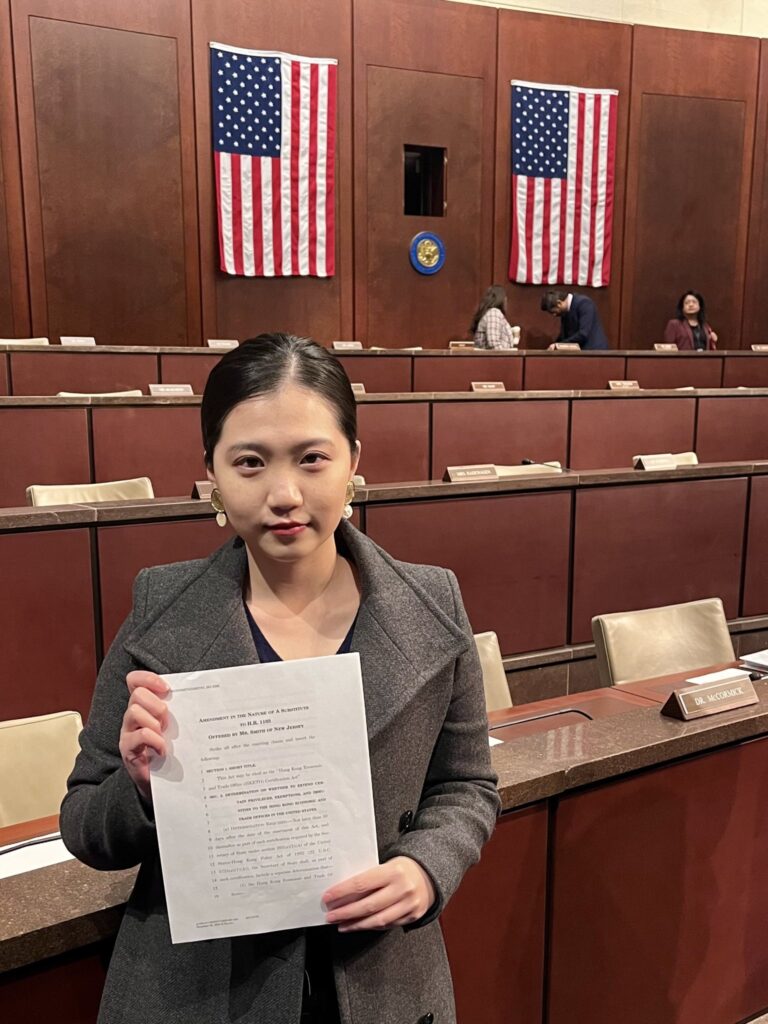

As executive director of the Hong Kong Democracy Council (HKDC), Anna focuses on international policy and diaspora mobilisation. She spearheads key policies like the “Renew and Expand D.E.D. for Hong Kongers” in the U.S. and organises global summits to unite Hong Kong exiles.

Anna, known for her decisiveness and eloquence, speaks with unwavering conviction. Behind her political presence, she once had different aspirations. She wanted to be a filmmaker. “I want to tell stories of human emotions. Inside each person lies a universe that ultimately connects with others.” Now, her storytelling carries the voice of a city that refuses to be forgotten.

Now 28, Anna reflects on the life she’s lived thus far, “A part of me is missing…a part I could only get back when I am back in Hong Kong one day.” Yet, exile forces her to seek a new kind of belonging. “The challenges and pain so far have taught me to look inward. It is a process and a training to become a better and fuller human.”

Chloe Cheung: The youngest voice in exile

At just 19, Chloe Cheung represents the youngest generation of Hongkongers forced into exile. Unlike Anna, who has found her role in international advocacy, Chloe is still trying to understand what it means to be an activist away from home.

Last year, she started working in The Committee for Freedom in Hong Kong Foundation (CFHK), meeting with advocates and politicians, lobbying and organising protests for Hongkongers abroad. These activities became part of her daily life, until, on Christmas Eve, a bounty was placed on her head, changing everything in an instant.

“People congratulated me, saying I was finally famous,” she recalls. “But seeing my name on the list, I felt shock, helplessness, frustration, and anger all at once, like my life had suddenly been rewritten.” At first, it didn’t feel real. But the weight of it follows her everywhere. She double-checks her surroundings, takes unfamiliar routes home, and wonders if strangers recognise her face. The fear never fades.

Yet she knows she cannot remain silent. “I refuse to let the government believe I am afraid. If those in Hong Kong can no longer raise their voices, then it falls on those of us in exile, who still have the privilege of free speech to speak on their behalf.”

Recently, Chloe tries to balance normal life with activism. The weight of exile is always there. “I have left Hong Kong, but leaving does not mean letting go, being far away does not mean betrayal.” She refuses to disappear. “The regime fears love, fears truth, and fears the voices of freedom, all because they are weak, they use fear to silence us. They have sentenced me to exile, declaring that I will never be able to return to Hong Kong for the rest of my life.”

Kacy: A life in between

In 2019, Kacy operated in Hong Kong’s underground activist network, working in the shadows to coordinate protests, communicate with other activists through a secured system, and move supplies between safe houses. She worked in the dark, keeping the movement alive. Now, she is caught between a past she can’t return to and a future she struggles to define.

Now a university student in the UK, she feels more distant from her past than ever. For years, she shut out news of Hong Kong as a survival instinct. “I thought I had moved on, but now I realise I never processed it. I just buried it deeper,” she admits. “I only learned to hide it.”

Most of her classmates are from mainland China. She speaks Mandarin daily, carefully choosing her words, yet the more she blends in, the more she feels herself disappearing. “I know I’m luckier than some, I get to go back to university,” she says. “But sitting in lecture halls, surrounded by classmates I can’t relate to, I feel like a stranger in my own life.”

When she speaks Cantonese on a phone call, she feels the weight of stares. Political discussions come up, and she stays silent — not because she doesn’t care, but because she doesn’t know if it’s safe.

One day, a mainland student made a cutting remark: “I hate all anti-communists. Taiwan and Hong Kong only want independence as they have nothing better to do now that they’ve made money. I know that you are not againsting the CCP, because you hang out with us.”

“I froze,” Kacy recalls. “I want to live a normal university life like everyone else. But after that day, I cried. I am angry at myself. I am here in the UK because I spoke up for Hong Kong’s freedom and democracy, but at that moment, out of fear of being alone, I said nothing.”

When her flatmates ask about going home, she lies because she no longer has one. “I just say the flight tickets are too expensive,” she admits. But the truth is, she has no home to return to. “I miss Hong Kong, and I miss the sense of belonging,” she says. “No matter how hard I try, it’s not the life I am searching for.”

Three women, one struggle

Though their circumstances differ, Anna, Chloe, and Kacy are bound by the same fate, displacement without resolution. One fights through policy, one through her presence in exile, and one is still searching for her place in the fight. Their struggle is not just about Hong Kong’s democracy, it is about surviving exile, resisting erasure, and finding a way forward in a world that may soon forget their homeland.

“When Hong Kong is liberated from the violence, harm, and threats of a tyranny, I will return immediately,” Anna states without hesitation. “Until then, exile is not a choice, it is a necessity.”

Despite the weight of exile, none of them surrender. For Anna, exile is not the end, it is only the beginning of a new fight. Looking ahead, she is certain that Hongkongers will continue to resist in new ways. “The movement will continue to evolve, it is already evolving with younger voices shaping its direction. I hope it becomes more egalitarian, where different voices take root and grow, one that fosters democratic deliberation and aligns itself with the shifting dynamics of international politics.”

Exile has scattered them, but it has not silenced them. Across continents, in different languages and spaces, they fight not just for Hong Kong, but for the right to demand freedom without fear. Their struggle is not only about returning home; it is about ensuring the world never forgets what was stolen. Because for them, exile is not just an absence, it is a defiance, a refusal to be erased.

For Kacy, exile is a path with no clear direction, one she is forced to navigate alone.

“We speak about freedom, yet I wonder if I will ever feel free. Even in exile, I struggle to belong. I miss Hong Kong, but I no longer know where home is.”

Chloe, however, refuses to let exile define her.

“I understand now, being a Hongkonger comes with a cost. But if I had to choose again, I would still walk this path.”