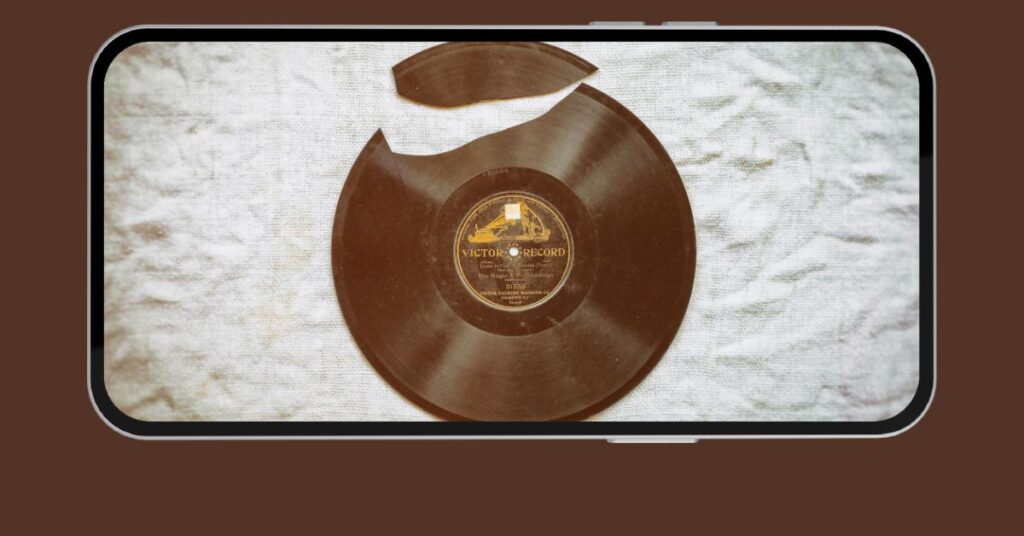

When Brian Brandt founded Mode Records in 1984 there was no such thing as music streaming. Instead, Brandt’s revenue was made mostly through selling the physical albums Mode produced at that time.

“I’m lucky that I lived through the really great times of the record business,” he says. “In those early couple of decades, it seemed to me anything was possible.” However, things wouldn’t always be so easy.

The illegal music piracy website Napster came right before the turn of the century, which hit Mode in terms of copyright and revenue. After three years, online streaming services started to appear and thrived in a digitalised internet environment.

Since then, it is streaming that generates the vast majority of the music industry’s revenue. According to data from the International Federation of the Phonographic Industry, streaming contributes to 65% of recorded music industry revenues worldwide in 2021, whereas the selling of physical records brings in less than 20% of total income.

However classical music is not benefitting as much as popular music genres. “Around 2000, before streaming, I could earn $6000 to $12000 a month just on North American sales. Now, the worldwide digital sales don’t even break $1000 most months,” says Brandt. “I can’t even earn enough from streaming each month to make a new record. I speak with some colleague labels and everybody has reduced their release schedule because the income stream is so small.”

“If you’re a major pop artist and you’re getting millions of hits in one song per month, of course, it adds up. But for classical music, what label really is getting that kind of traction?”

Brian Brandt, founder and CEO of Mode Records

One reason is the “pay per stream” mechanism used by streaming platforms like Spotify. Every time a song is streamed on Spotify, the company will pay the label that owns the song. However, one movement of classical music is normally much longer than a pop song. So, for the same period of time, a pop song could be played several times more often.

According to Brandt, the average income per stream is typically around 0.006 of a cent (around 0.005 pence). “If you’re a major pop artist and you’re getting millions of hits in one song per month, and that’s just one piece of your big catalogue, of course, it adds up. But for classical music, what label really is getting that kind of traction?” he added.

While the total income of Mode has decreased, Brandt says that the streams of music from Mode have gone up. The numbers have risen from a few thousand to 30,000 and sometimes 3 million over the years, with this rise not reflected in its streaming income.

“A big part of the problem seems to be TikTok,” he says. “The income from TikTok is literally zero. People can use your music in their videos, but somehow they don’t have to pay for it. All of a sudden, you’re getting 3 million digital hits, and your income is going down.

“I don’t know if there’s anything that we [the music industry] can do. Probably the three major labels, which comprise so many labels inside of them, have figured out a way to make it work for them.”

Read: Five ways to boost your income as a classical music student

Read more from our future voices here

With small and medium-sized classical music labels being hit badly by the trend of digitisation, many are trying to find a way out. Sergey Bryukhno, CEO of Oclassica, a digital-only classical label based in Estonia and founded in 2010, says that these labels need to adapt to the changing landscape. “We live in a digital society where change is constant. Those involved in classical music need to align their vision with the modern era and let go of legacy thinking.”

Bryukhno believes that the trend of streaming is irreversible because future classical music listeners will grow used to it. “When we look at the statistics, the majority of classical music listeners are aged 50 and above,” he says. “The userbase of music streaming services is continually growing and ageing, approaching the core demographic group of classical music lovers. Additionally, these services are constantly improving the quality of streaming.”

Klaus Heymann, the founder of Naxos Records, a classical label based in Hong Kong and founded in 1987, offered some survival rules for labels in the streaming age in an interview with Rhinegold Publishing in 2015. His suggestions included providing a broader catalogue, trying to put music works into playlists on streaming platforms and not giving new releases to streamers.

Heymann also pointed out the need for labels to work with streaming services and the aggregators who supply the services to survive. Brandt echoes this, bringing up the recent Hollywood writers’ strike. “It is an example of taking proper proactive action before it is too late.”