A profession viewed by many as reliant on male physiology and a machismo temperament, to take on the job as door security as a woman or non-binary person presents a host of challenges. In the city of Bristol, however, one organisation is working to change the professional landscape of security work for the better.

To put on a hi-viz tabard, display a Security Industry Authority (SIA) licence card and to assume the role of a door security officer as a woman or non-binary person in the UK is not easy.

It is to subject oneself to staggering levels of work-place prejudice, coming either from the management of the venue you’ve been assigned to protect for the evening, or the distrustful public in attendance who see you as an obstacle to their tumultuous brand of after-hours fun.

According to data published by the SIA on the UK government website (a body which grants you a license to work in security upon gaining appropriate qualifications), in the period between 2015-2020 a lowly average of 9.9% of those with a license were women. Compared to recent data, this number has risen to 12% as of Spring 2023. Why is there such a gender imbalance in the industry? How does this shape the experiences of women and non-binary people in the role, and experiences of the party-going public?

The conversation starts with Freya (she/her), 22-year-old former SIA personnel. Having worked in pubs, clubs and events throughout the cities of Bristol and Bath and resolute in herprevious experience in event work at some of the biggest festivals in the world, Freya’s approach to the job was different.

“For me, I just wanted to see people have a good time. That was the most important thing, literally just making people feel safe, and heard. I’ve had so many instances in venues where a senseless, masculine approach was just not right for the situation.”

Describing an incident in which she, alongside a younger male colleague who was freshly licensed at a pub in North Bristol had to intervene in a fight, Freya says the idea that one must be masculine and powerful to do the job of a security officer feeds into the minds of men who join the SIA. The preconception, according to Freya, encourages a tendency in her male colleagues to think with their ego and abuse their security status on the frontline. In this incident specifically, a fight broke out between long standing patrons of the pub, with a history of conflict. Her male colleague used physical intervention immediately to separate the two and force who he believed to be the instigator out of the premises, something which Freya says should be an absolute last resort.

“He screamed at the woman; she felt threatened and screamed back, trying to explain her part in the situation, but he wouldn’t have it. What followed was a horrible scuffle, the woman burst into tears and sat down outside to decompress with a cigarette.

“Shortly after, I went and spoke to her myself, impartial in my approach. Turns out the fight started as an accident when she opened the front door to enter the pub as the woman she fought with was stood in front of it. She interpreted this as instigation – but it was an accident.”

Freya admitted their troubled history didn’t help, but ultimately it was no one’s fault, and no more intervention was needed oncethey’d been separated and left to sit on opposite sides of the pub.

“I wouldn’t have found that out if I hadn’t have taken the time to speak to her. When you work with people, everything is about communication – everything. We are trained to use conciliatory body language and in the first instance verbally de-escalate the situation as best we can, only to use physical force if our and other members of the public’s safety is threatened. I tried to explain this to my colleague, and do you know what he said?

“How can you stand here telling me how to do the job? I am a man, you are woman. I’m the only one of the two of us who can be trusted to keep this place safe, all you do is stand there and look pretty.”

In spite of Freya’s experience and more skillful application of training, her male colleague assumed superiority over her when it came to security work, but he was banned from working on the premises as a result of his handling of the incident after it was reported. This is just one in a long list of misogynistic experiences Freya had while working on the doors.

“I’ve been sexually assaulted, picked up and thrown about by drunk arrogant men, ignored and laughed at by punters – men and women, mocked by venue management, often times while working to safeguard a venue completely on my own.”

The synonymity in expectations of what traits someone mustexhibit to do the job properly, both in the crowd and venue management, means female bouncers are battling two frontiers when it came to doing their job. The fact her male counterparts were being perceived as able to offer more in terms of brute force and their confidence in knowing that did make for a more submissive crowd of an evening, which kept management happy.

To those who participate in urban nightlife and those who provide the club space, there is an unspoken mutual arrangement between security and punters that keeps everything running smoothly. Male security officers don’t mess around, and they can and will deal with you if need be, and so the public know to behave around them, hide their drug stashes and engage in dishonest behaviour to preserve their enjoyment of an event in spite of them. The system seems to work, but because of it, Freya left the role after less than two years.

Every shift is different, but you should always want to bring the best out of people. This is what it’s about.

Nicky, 56, SIA licence holder

Nicky (she/her), 56, is a female SIA license holder also working in Bristol and the South-West with decades of experience in the role. Although not citing her gender as having been an issue for her over the years, she agrees that a person-centric rather than compliance-thirsty approach is better for everyone.

“One of the things I think is true about any SIA licensed position is that everyone involved has a different view about what that position should involve: meeting licensing conditions, actually meeting the expectations of the people you’re ‘supposedly’ crowd controllingand how we will keep these people happy and rock’n’rolling, as well as keeping the fights and negativity outside the venue, you know, vibing.

“Something that’s kept me alive is knowing that saying: if you don’t what you stand for, you stand for absolutely anything. When I’m stood in position, I know there’s things I want to see like non-discriminatory practices, I want new people to find a bridge to each other on the dancefloor in a way they wouldn’t anywhere else in life. That’s my personal instinct. And then there’s discerning what the customer expects alongside the local authority requirements, and the identifying the trigger points that build up in the crowd that you’re controlling.”

Like Freya, Nicky describes having to tow a line between meeting the requirements of legislation and venues bosses, and managing the reality of how people behave when they’re having fun. There is a slight contradiction between what she as a person can bring to the role, and what is expected of her. She notes that you’re only as good as the crowd you’re working with, nodding to the December ‘22 crowd crush at Brixton’s O2, resulting in the deaths of 2 people, one of them being SIA personnel.

“Every shift is different, but you should always want to bring the best out of people. This is what it’s about. Connect with them as a human being, don’t make them feel small with petty confiscations, unnecessary confrontation or exercises of power. Always respect the attendees you serve to protect.”

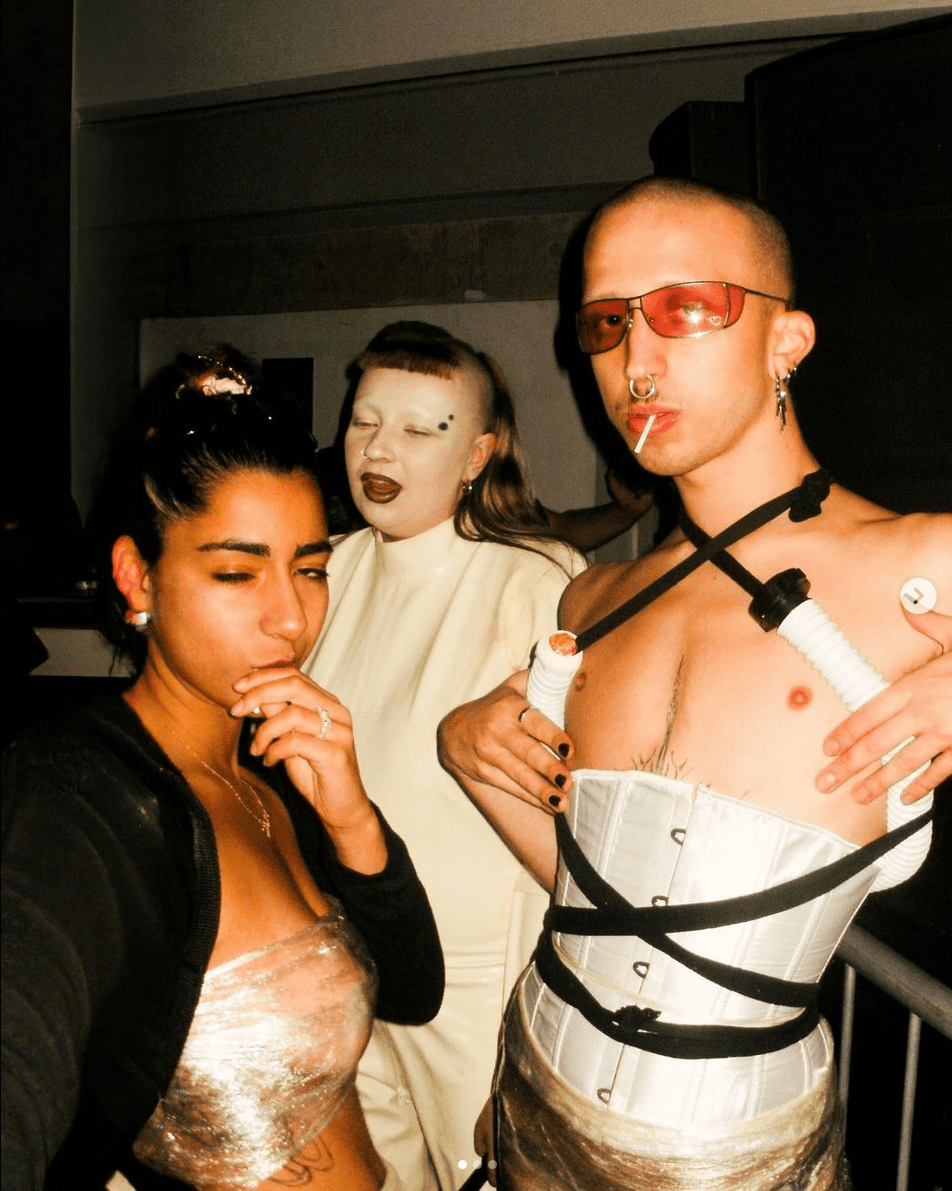

In 2022, a new collective was established by an employee of Lost Horizon. Just on the edge of the City’s centre, Lost Horizon is an independent arts centre in Bristol which showcases art and performance, promotes protest and free speech, and a offers a diverse live music program inside a warehouse with walls plastered in a psychedelic array of pink and purple event posters. This collective is called PHAT (Poland Has A Task).

Run by former events promoter and record label manager, Ola (they/them), 25, the organisation’s acronymous name signals the decline of support for queer rights in Poland, home country of Ola. A political trajectory of which they are strongly opposed, Ola’s activism in support of queer rights has taken many forms, first influencing her work as a promoter, then prompting the release of charity album. Now, this work manifests as a women-and-femme-queer security and welfare agency.

“PHAT started off as a welfare agency in which we would work alongside other teams of licensed security personnel to provide more personable support for attendees of a particular club or event, providing safe spaces, counsel, drug testing equipment and contraception. We have recently expanded our service, and now PHAT takes a hybrid form seeking to provide the security that will reassure and protect the host venues of an event, but preserve our roots in welfare which puts the attendees first.

“Most importantly, PHAT works to address the disproportionate representation of women, non-binary and femme-queer people in the security industry in the UK. Some might argue that our employment regime is exclusionary, but we, alongside other collectives such as London-based Safe Only LTD are simply looking to reorientate the industry. This is by encouraging women and queer people with a passion for events to sign up to an agency where they know they won’t suffer from workplace prejudice.”

On the ground and in select clubs in Bristol, PHAT offers more than sentries planted on pub doorsteps and on the corners of dance floors. Often booked in to work an event that caters to a queer crowd, PHAT staff can identify on a more fundamental level to punters and provide more meaningful care than “a straight, 50-year-old man who’s been out of the party circuit for decades and who doesn’t know anything about modern gender politics,” as Ola puts it.

Instead of looking to impress the management of a particular venue, PHAT’s workforce looks to accommodate those in attendance, with a particular focus on drug-related harm reduction, a more diplomatic approach to conflict management, even going so far as to offer tea and biscuits and quieter spaces to attendees who find themselves overwhelmed by the party space.

Working with The Loop and Bristol Nights, a Bristol-based organisation which seeks to establish “a city-wide policy to reduce the risk of harm from alcohol and other substances,” PHAT is helping to start an honest discussion about the use of drugs across the city’s venues. Aiming to bring Bristol’s licensed operators, event promoters and festival organisers together, along with nightlife workers who face the dancing masses, they want to “dispel myths and assumptions” that prevent people accessing appropriate care in drug emergencies, according to their promotional material.

Consequently, PHAT’s staff are well versed in the symptoms of contra-indication and ill-advisable drug combinations. While – by law – they are required to conduct bag searches upon entry into venues, they still make efforts to reassure the public that if they have smuggled in illegal substances and become ill after taking them, they are the people to go to for non-judgmental help. It is stressed to attedees that they do not serve as an extension of the police.

If people want to learn and are up for the conversation, that’s the only thing that matters. We are better together.

Ola, founder of PHAT Bristol

Ola notes that the impact PHAT has had on the city in just under a year of operating in its current form is huge.

“We are lucky in Bristol in that the city is full of grass-roots venues that are looking to try something new for their customers. PHAT’s approach is spreading; we are getting booked for events which aren’t strictly aimed at queer individuals, which is fantastic. It means our working culture is being commended and normalised. We have found that our approach to security work encourages punters to return to venues again and again, given that they know the people charged with looking after them are respectful, trusting, and a right laugh – we are party goers ourselves!”

While PHAT’s identity is predominantly femme-queer, Ola reports they are more than open to working with security teams in which the workforce is not as diverse.

“One thing which goes against everything we stand for is the annexing of the queer community. By being overly-activist, closed off and unapproachable to teams that don’t share our values, we would risk forming another divide in the industry. We will work with anyone who embraces us; we have a lot we would like to share, and lots we would like to find out about ourselves as a relatively new collective. If people want to learn and are up for the conversation, that’s the only thing that matters. We are better together.”

If the next few years prove to be successful for Ola and the PHAT collective, Bristol could be witness to a radical transformation in the party landscape of the city, in which the scene is super-charged with diversity, inclusivity and trust among venues, patrons and the police.

They boldly represent a rejection of the current systems of the UK security industry, its rigid adherence to the gender binary and its favour towards men. An organisational game-changer, PHAT is fast evoking change to the industry for the better.