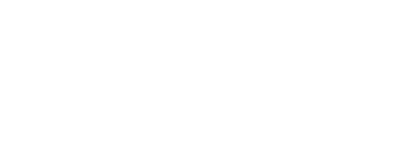

Omidán Irẹnítèmi Alabi has four deep incisions on the left side of her face. It is a noticeable feature on an otherwise baby-faced, clear-skinned woman in her late twenties. Sobbing in her Lagos home, she is open about attempting to end her life three times. “If I had known about this at an age when I was more aware, I would have rejected it. I feel like when I was younger it blocked opportunities for me and created insecurities.”

Omidán’s marks are permanent. And according to her, people with these scars are perceived as backwards and not deserving of all life has to offer. During our conversation, she makes it clear this ranges from a functioning love life to a supportive family and career prospects.

Prominent Nigerian ethnic groups, especially those of Yoruba heritage, have used facial markings for centuries to mark their tribal background. They do this by using sharp objects to cut and burn the skin. For some, it’s a rural practice now shunned by those in the bustling urban centres of the country. For others, it’s an unshakeable part of their identity, one they are determined to maintain as a key part of Nigerian culture.

The year 2003 marked a turning point in Nigeria, as federal law banned the act of scarification, or tribal marking, on infants. Twenty years on, from Lagos to Maiduguri, are attitudes to tribal marks changing? And how are those with the scars living their lives?

As one of 24 children born into a polygamous family, with her father having seven wives, Omidán says her marks were given to her to ensure nobody could say she was not one of her father’s children. This is why she has not sought help to erase the marks.

Omidán admits being part of such a big family led to alienation and she did not always have enough attention growing up, but this is a unique part of her. “My dad passed away some time ago. I need [the scars] to keep the memory and a piece of my father with me,” says Omidán, whose family hails from Oyo State. “When I have my first child, I don’t think I will give them tribal marks because I’m not sure they will be able to bear what I went through, and I think it’s unfair to do that to a child.”

“I’ve even been told ‘you are not that beautiful, especially with that thing on your face”

Staying close to home, Omidán’s “stepsister by tribal marks,” Adetutu Alabi, a single mother living in Lagos, speaks with a recognisable hopelessness. Adetutu openly admits her lack of self-worth bled into her romantic life. “There are red flags that I note when I am dating, like people who only want to be out with you when it is dark. I’ve even been told ‘you are not that beautiful, especially with that thing on your face,’ but at least I have two kids [14-year-old and 18-months-old] to worry about,” says Adetutu. “So, I don’t have to think about dating anybody and what they think about me. I’m just focused on ‘japa japa’ with my kids, taking them abroad and making them my best friends.”

Life has been particularly difficult for Adetutu. “Going to school was when I first realised I had something on my face that people didn’t understand,” she says. “‘Did you have a fight with a lion? Did a cat scratch you?’ You know how kids can be. They would tell me ‘don’t play with us, you are a witch,’ so it really shattered my self-esteem.”

Adetutu says her tribal marks may have been given on the traditional Yoruba date of seven days old, which is also when an infant is named. After conversations with her father, he explained the family’s markings were a form of “identification and beautification”. Historically, it is believed markings were a way to identify those from different tribes during the Transatlantic slave trade. The marks on Adetutu’s face are known to the Oyo people in Southwestern Nigeria as Keke or Gombo.

She led a popular social media campaign in 2018 called “tribal marks challenge”, which garnered attention from Rihanna. Adetutu put one of her modelling pictures alongside a picture of Rihanna and it went viral, leading to the singer following her on Instagram. Even though she’s disappointed it’s not ignited a modelling career, Adetutu says she’s proud that she was able to “show other girls with tribal marks you can do anything” and change the attitudes she faced growing up in Lagos.

In Nigeria, there are over 200 ethnic groups and they all have different reasons for marking skin. “The marks we have today, in the absence of another means of identification, are for recognition. They served as identification for persons of royal lineage and ethnic origin in general,” says professor Kokunre Agbontaen-Eghafona, a cultural anthropologist who’s studied Nigerian traditions for 25 years.

In what was formerly known as the Benin Kingdom, the practice was so common that if you did not have scars, you could not access the Oba palace because the marks were seen as sacred. In the north, marks are a sign of beauty to the Wodaabe women. The more you mark your face, the higher your pain threshold, which demonstrates your ability to bear children. The men scar their faces when they hunt for food because they believe it protects them from opportunistic predators.

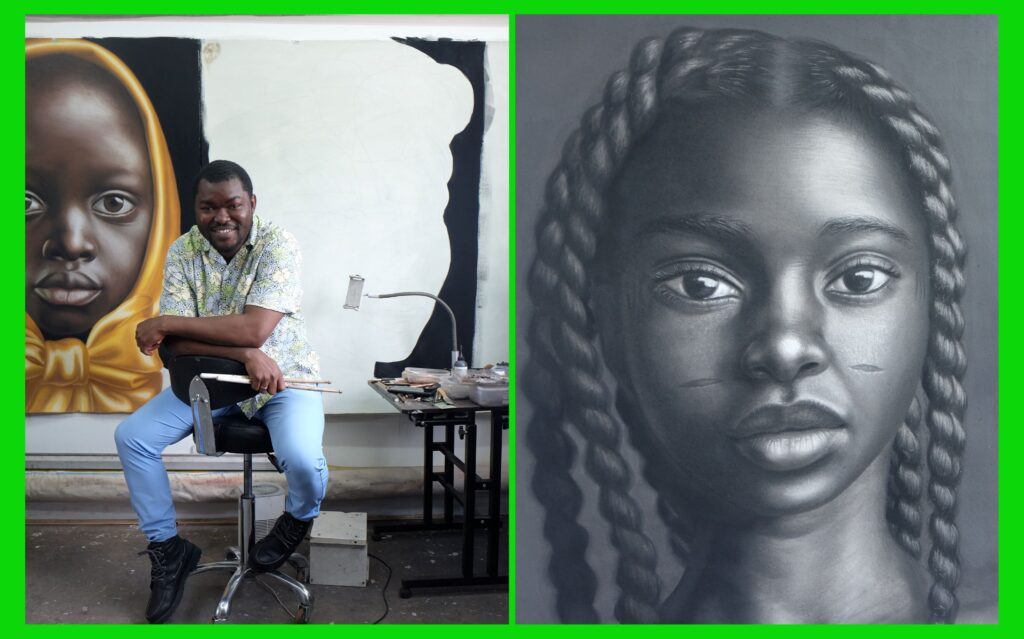

Many of these details became apparent to botanist turned self-taught artist Babajide Olatunji during the research for his critically acclaimed Tribal Marks series. The exhibition uses hyper-realism to represent scarification, particularly the practices of Babajide’s Yoruba ethnicity, and interactions with the carriers of these marks. Babajide says he ventured all over Africa to create his work, which has been featured in numerous galleries across the globe.

Babajide says his main aim was to explore the nature and nurture aspects of the scarification phenomenon. “Scars are like fingerprints for them; they tell you exactly who you are and exactly what you’re going to be,” says the painter who also gains inspiration from previously studying plants. “In Yoruba religion, there are plants associated with the worship of each God — Oshun, Oya and Olókun. How precise this sense of identity is and how it attunes you to set behaviours and expectations fed its way into this project.”

So, what is the consensus on tribal marks these days? Kokunre has a clear assessment. “The marks are now seen as anachronistic. People with these marks are looked upon as old-fashioned,” she says. “However, where smaller marks are seen on the face, they tend to be for therapeutic and indigenous medicinal purposes.”

Many Nigerian cultures now practise scarification on hidden parts of the body, says Omidán, reflecting its transition to being seen as taboo. She insists more needs to be done for the representation of people with tribal marks in Nigerian popular culture. Nigerian cinema, Nollywood, is now the second largest film industry in the world behind India’s Bollywood, by volume of films made. “Two of last year’s biggest films, Ijakumo and Anikulapo, used makeup to give the actors tribal marks but did not use the real actors with tribal scars,” she says. “People need to see the inner beauty and start endorsing body positivity around tribal marks.”

Twenty years later, the lines of social acceptability are still blurred. Those who bear the marks on their face daily but are being told to leave their custom behind are still finding new ways to celebrate their unique feature. Maybe one day Adetutu and Omidán’s scars will be viewed as “normal tattoos”.

Picture: Omidán Irẹnítèmi Alabi

You may also like

-

Why effective acne treatment is becoming inaccessible

-

Inked up and blacked out: extreme cover ups

-

Six black photography exhibitions you cannot miss this summer

-

Black, nasty, mad fat: why is there still no space for dark-skinned female rappers?

-

In the spotlight: three drag performers painting their identities through makeup