“Looking at my old camera phone, I’d look dark and really washed out … you can only see my teeth!” chuckles TV presenter AJ Odudu as she advertises the newest Google Pixel phone, which promises a “real tone” feature that uses artificial intelligence to take better pictures of people with darker skin tones. Companies like Apple and Samsung are now incorporating “real tone” technology in their phones to promote diversity and appeal to more customers. For people of colour, working out how to appropriately light their skin on camera is still a familiar problem. Poor lighting can lead to grainy photos but excessive lighting can lead to overexposure and images that look over-edited.

Part of the problem faced by photographers is the slow rate at which technology has developed to adequately light darker skin tones. So why have cameras taken so long to reflect modern reality?

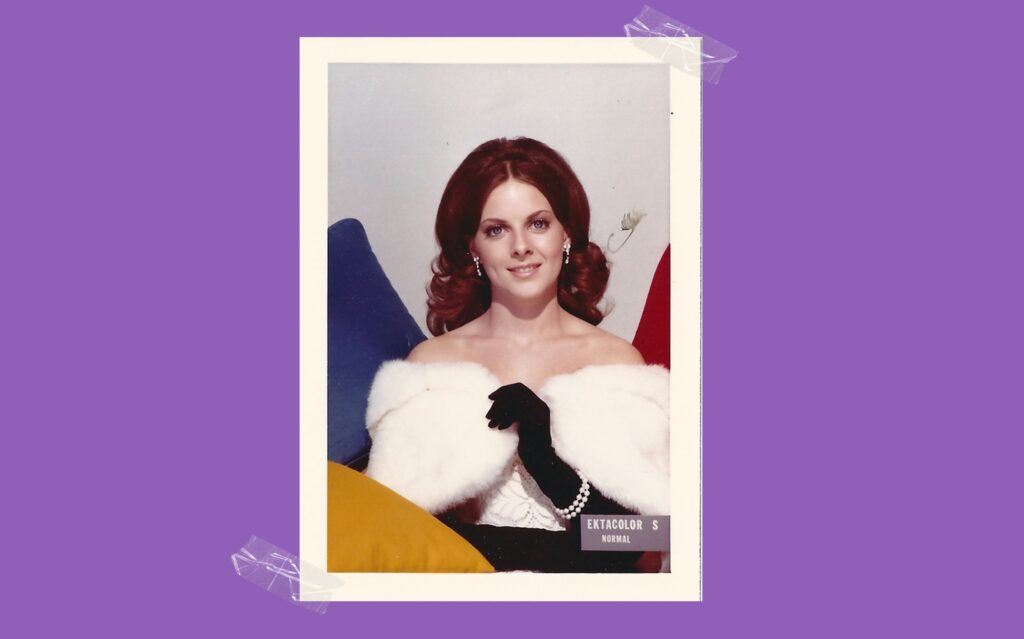

Historically, photos were developed from what was known as the Shirley card — the generalised skin standard for colour film toning in the 1950s from Kodak, where the subject was always a white woman. Colour film consists of colour-sensitive layers stacked on top of each other, with a series of chemicals to develop them once exposed to light, creating the film’s colour balance. For many decades, any appearance of red, yellow and brown tones were left out, setting back progress in representing a diverse range of skin tones. Kodak started testing cards with black women in the 1970s with GoldMax, a film advertised as being able to photograph “a dark horse in low light,” a racially charged turn of phrase. Even though it is no longer used, there are still racial undertones in photography.

Lorna Roth, a communications studies professor, published studies analysing the way skin has been shown for more than a decade. She says there was a “light skin bias” in digital camera design and film development technology, causing the rendering of non-white skin tones “highly deficient”.

Black photographers tell SKiN how to properly capture darker skin tones. You don’t have to be a pro, anyone can do it.

Establish a relationship with your subject

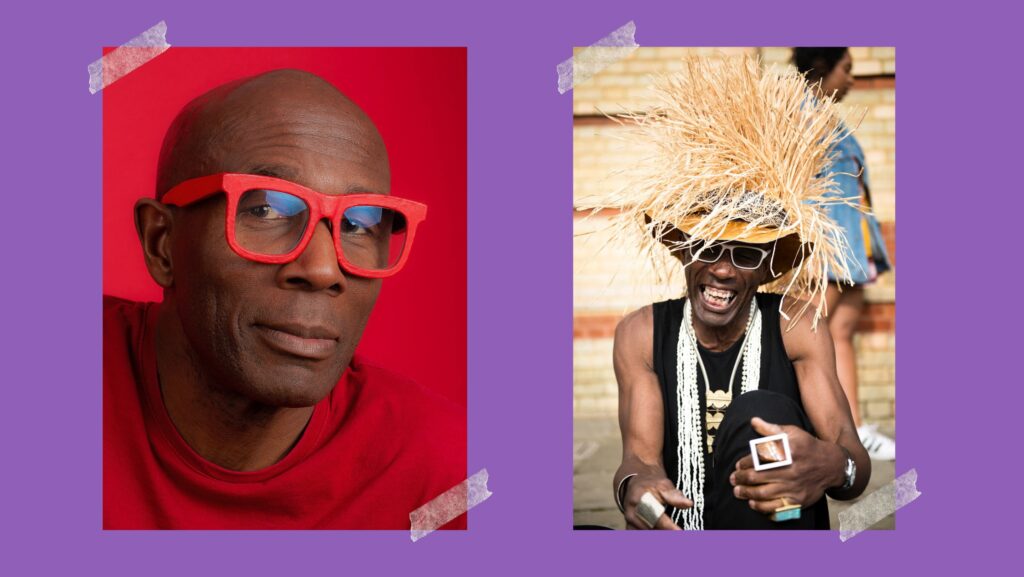

Robert Taylor, a professional photographer for over 40 years, says the process is all about “controlling where and how light falls on the skin.” Robert’s commercial practice is portraiture, and his artistry centres on race, identity, and expression of sexuality. His most recent project, Permissible Beauty, a visual installation at Hampton Court Palace, re-examines the narrow beauty standards of the 17th century. The exhibition reimagines 10 portraits of women at the court of King Charles II as queer black women.

Robert believes collaboration is at the heart of successful photography of black skin. “I’m proud that a core black team organised the project. An English institution opened itself up to a black conversation and not the other way around.” He conducted in-depth interviews with each of his subjects and is a big believer in trial and error. This helped create an “authentic black presence” by allowing the person being photographed to have as much input as possible. The aim of taking photos should be to capture the energy of a living person rather than seeing them as just an object.

Robert’s technical tip: Don’t retouch pictures after they are taken. “Lab time should be restricted and any blemishes from the natural picture should be kept in.”

Get to know your camera and make your environment work for you

“My first trusty camera was a Canon SD mark two. I had that for 12 years, but one of the things I struggled with the most was lighting black skin properly. It was either overexposed or people’s skin features were too dark to be recognised,” says Gifty Dzenyo, a talented photographer whose work was included in 2021’s Black British female photographers’ exhibition in Walsall — the first of its kind.

Some companies have used makeup with SPF to aid better reflections for photographers when taking pictures of skin, but Gifty believes knowing your camera well and changing where and how you shoot is of equal importance. “Soft light works well for black skin, and it’s widely thought that direct sunlight when taking photos of dark skin is not conducive to capturing a great image,” she says.

Gifty’s technical tip: Know how to pivot if it isn’t working. “You might need to move the person, move yourself, find angles. I’ve found success using a reflector to bounce light in a way that flatters the subject. You need to be honest and see if something is working. Change tact straight away and know how to pivot if it isn’t working.”

Mitigating factors matter

Photographer Daniel Oluwatobi has had a whirlwind start to his career. After being given the opportunity by Live Nation to photograph an Ella Mai concert in late 2018, his career has only gone from strength to strength. The list of household names he has photographed includes Burna Boy, Janelle Monae, Lizzo, and Solange.

Although Daniel speaks of access to spaces as being a major obstacle to his growth in the industry, he believes his albinism has helped people see how good he is. “I get asked how I take pictures because I’m partially sighted,” he says, referring to his nystagmus — a symptom of his condition which not only affects the pigment of his skin but his eyesight as well. “Glasses help but don’t correct the issue,” he explains. “You must adapt to the situation. The way I tell the story of an event, I give myself time to get the perfect shot.” In these cases, he gives less precedence to the camera and more on what he can control.

Better cameras mean better results, but this is not enough. The mentality needs to shift from “shooting dark skin is difficult” to “shooting dark skin is just different”.

Daniel’s technical tip: Don’t overdo it with the flash in nightlife photography. “I found that I don’t shoot with flash as it’s too harsh, but there would always be a spot where light from the venue would hit everyone and I’d wait for that moment to get a more natural shot.”

Thanks Morgan. I recognise this difficulty, particularly when taking photos that have both white and black people

together in the frame – really tricky.