The novelist from Prague has Gen Z in a chokehold, but any algorithm-induced obsession has its limits.

Among the things that tormented Franz Kafka in 1912 were his authoritarian father, social alienation and a story that ‘came to him in his misery lying in bed’ – or at least that’s what he told his soon-to-be fiancé, Felice Bauer. Following a three-week bout with writer’s block, The Metamorphosis (Die Verwandlung) – a ‘bug piece’ (Wanzensache) that would outlive the Czech novelist – was born.

The characteristically nightmarish novella centres around overworked salesman Gregor Samsa, who one morning wakes to find himself transformed into a gigantic insect. Over a century later, The Metamorphosis is making waves in unlikely places. From fancams on TikTok to Kafka-themed birthday cakes on Twitter, young people took to social media to pay homage to the heart-wrenching writer. This begs the question: what do Gen Z and a luminary of twentieth-century literature have in common?

An arthropodan transformation doesn’t ring any bells, but the undercurrent of social isolation that runs through Kafka’s oeuvre hits too close to home. Come to think of it: while Samsa spent the better part of The Metamorphosis imprisoned in bed, we spent the better part of 2022 in a polarising lockdown. Isn’t a global pandemic as perplexing as a grotesque metamorphosis? Considering that it prefaced a cost-of-living crisis that would exacerbate pre-existing anxieties, it’s reasonable to say that modern existence is disconcertingly Kafkaesque.

“Kafka was clearly a point of reference for many people during the pandemic, especially with The Metamorphosis,” said Dr Karolina Watroba, a post-doctoral research fellow in Modern Languages at All Souls College at University of Oxford. “I have a whole section about it in my forthcoming book Metamorphoses: In Search of Franz Kafka. Many readers reported rereading the story as a reflection of life in lockdown and estrangement from one’s own body, and there were multiple adaptations in other media that reinterpreted the story in this light.”

Watroba pays heed to the parallels between “German-speaking Europe in the 1920s” and recent times. “Kafka himself fell very ill during the influenza pandemic of 1918, which was widely compared to COVID-19, and he ultimately died of another serious respiratory illness, tuberculosis,” she said. “I haven’t seen such parallels being made to the current economic crisis – at least not yet – but it is interesting to note that Kafka also lived in Berlin in the last year of his life during hyperinflation that peaked in 1923.”

The pandemic helped loosen the grip performativity had on Gen Z. We all knew there was no going past our front doors; there was no point pretending otherwise on Instagram. From then on, the facade of social media began to wane, with blurry photo dumps and ‘shitposting’ accounts overthrowing perfectly-curated feeds. Gone are the days of VSCO filters and FaceTune subscriptions; we now live in a collective ‘flop era’ where it’s normal – honourable even – to admit that you haven’t left your bed in 24 hours. On the road to authenticity, Gen Z made a pit stop to read Kafka, whose writing embodies the candour they’ve been hankering after.

“Kafka was actually a lawyer by training and you can see that he writes like a lawyer. It’s very clear. It’s very simple. It’s not fancy or expressive. There’s a timelessness to that,” said Professor Carolin Duttlinger, co-director of the Oxford Kafka Research Centre and professor of German Literature in Wadham College at University of Oxford. Coincidentally, she was a teenager when she first encountered Kafka and recalls being “immediately fascinated.” She adds, “He doesn’t go about a project knowing how it’s going to end. That’s one of the fascinating things about him: he embarks on this journey and you embark on it with him. And so, you don’t feel like someone is trying to teach you something or they’ve got some sort of message behind their work. It’s totally unpredictable.”

Kafka’s plain-spoken prose proves that he was not afraid to say things as they were – even if that meant bidding adieu to happy endings. This also means that his novels, no matter how bizarrely premised, are digestible to the average reader of, say, 16 years old. The Metamorphosis, his lengthiest publication, is only 80-pages long, yet has the potency of a 600-page novel.

As Duttlinger points out, “I don’t think you really need to know much about the politics or the society [at the time they were written] because they’re such universal texts.” Kafka was not so much transfixed by external forces as he was by internal feelings. Duttlinger offers a Marxist reading of the author, suggesting Kafka was fascinated by capitalism, “and the dream of rags to riches. But he’s also very open about the exploitation that’s going on, the dehumanised existence people lead, how people give up their own identity to fit into models of what they should become.” His stories stand the test of time because they are anchored in human emotion, which shifts at a much slower rate than the outer world.

Plenty has changed since The Metamorphosis was published in 1915, but the existentialism that Kafka writes about endures. “I do think that reading Kafka teaches us something,” said Duttlinger. “Maybe not about ourselves, but about human beings: how people think, our ability to deceive ourselves, to lie to ourselves. I think that’s a very powerful feature. They’re great journeys into the human mind. They’re less about what happens on the outside.”

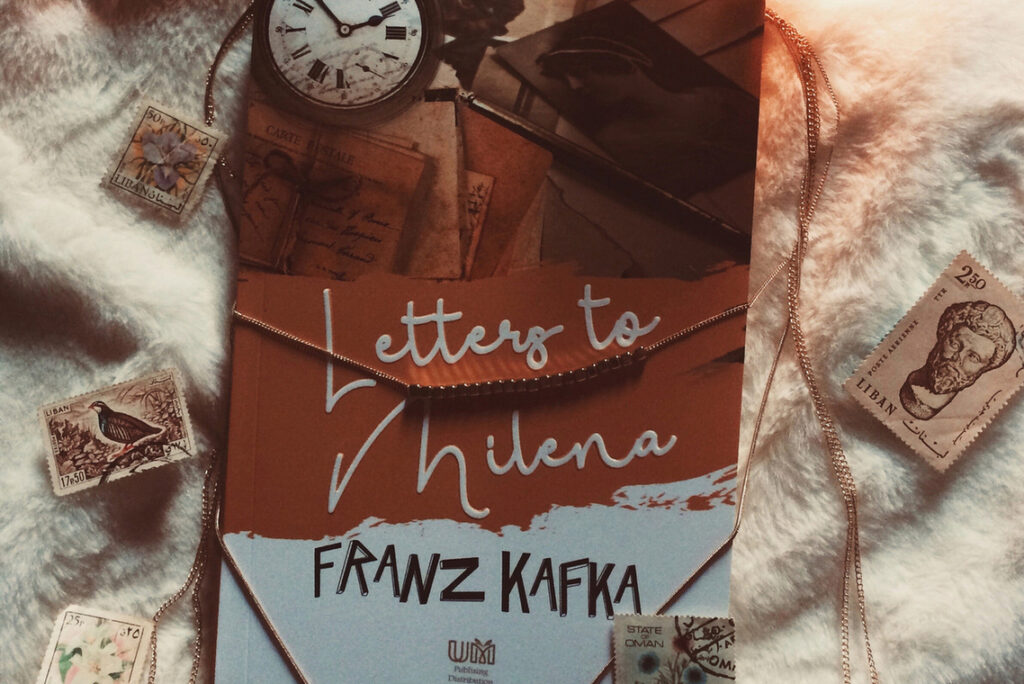

The hashtag #kafka has amassed over 143 million views on TikTok at the time of writing. Gen Z’s adoration is clear as day, with one-liner captions like: ‘I feel Kafka in my soul.’ Another user wrote: ‘This man has my heart’. If you haven’t seen a fast-paced montage of Kafka’s portraits and manuscripts, you’ll likely stumble upon romantic quotes pulled from Letters To Milena (1952).

For Gen Zers, Letters To Milena rekindles a lost sense of chivalry. It sets the standard for matters of the heart, appointing Kafka as an ideal partner. In February of this year, the Daily Mail referred to him as ‘an unlikely heartthrob on TikTok’. True enough, TikTok user Margarita (@aquariouscat444) posted a video emblazoned with the text: ‘You are out here being excited over a stinky ugly uneducated man texting you back when Kafka wrote “I can’t hold enough of you in my hands” to Milena’. Her caption reads, ‘If the guy you like isn’t WORSHIPPING you then pls don’t waste your time’. There is no shortage of comments that describe Milena as lucky. But I’d be remiss not to mention that Kafka didn’t exactly worship women.

For starters, Milena was a married woman. Kafka, on the other hand, died unmarried. However, Watroba reveals that he had “serious relationships with four women. He got engaged with two of them – twice with one – and broke off all these engagements.” Suffice to say, commitment was difficult terrain for the novelist. “He was secretly horrified by middle class rituals, of what it means to be a married man, a father and a business owner,” Duttlinger said.

Alongside Letters to Milena are Letters to Felice (1967), his former fiancé. “There are many moving and intimate passages in these letters, which suggest that Kafka respected and appreciated these two women, also in ways that were not a given at the time,” Watroba admits. “For example, in both cases he admired and valued their professional activities.” Pleasantries aside, she observes that “other passages in Kafka’s letters come across as rather insensitive, self-centred or possessive.”

“I always feel somewhat uncomfortable reading these letters, partly because they were clearly never intended for publication and so reading them feels invasive and voyeuristic on some level, but also because of how the book editions of these letters frame the women,” said Watroba. “Their responses to Kafka’s letters are largely unknown and the titles of the book editions only use their first names. […] Kafka is always Kafka, whereas Bauer and Jesenská are usually Felice and Milena. This unfortunately makes it too easy to overlook the fact that, just like Kafka himself, these women were fully fledged individuals with their own lives, interests and opinions.” Hear, hear.

Social media is due credit for breathing new life into Kafka. Just as his style of writing makes heavy themes manageable, TikTok’s quick-witted nature makes twentieth-century literature relatable. Indeed, Gen Z’s absurdist humour bridges the gap between one epoch and the next. But what does it mean to leave a man’s legacy up to the almighty algorithm?

Names as ubiquitous as Franz Kafka tend to be simplified into a meme, personality trait or dark academia trend. An excerpt or, in Twitter’s case, a beetle with an edited décolletage has greater potential for virality than a long-winded account of Kafka’s romantic relationships. Perhaps, that’s the problem: we use a singular quote to represent the full scope of his being. We forget the humanity behind the name. We romanticise the story, be it The Metamorphosis or Letters To Milena, without reading it from cover to cover.

“It’s almost impossible to find people who have never heard of Kafka,” Duttlinger concurs. “Everyone thinks they know about him already, which is both a plus and a minus. Because I think the first thing you then do is [avoid putting] him into all these boxes and to [instead] actually read the words on the page. That’s all we have really.”

All images, Ⓒ unsplash and pexels.