Torie Fisher had just arrived at the Atlantic City Beer festival when a man yelled: “There’s no way she’s the brewer!” Not only is Fisher the brewer, she and her wife have been running Blackward Flag Brewing for almost a decade. Fisher is not the first woman to experience this – when two customers at the Traffic Jam & Snug brewpub in Detroit asked to talk to the brewer and Chelsea Piner appeared, they chuckled: “Oh no, sweetheart, we wanted to talk to the brewer!”.

The beer world has not always been like this. In fact, if when thinking of beer, images of white bearded men in flannel shirts and £100-Carrhart overalls come to mind, consider that the history of beer is actually filled with goddesses, women and cats. How did women get booted out of the narrative?

Sara Barton, founder of Brewster’s Brewery and the first woman to win the British Brewer of the Year award in 2012, says: “Over eons and through civilisations, women had brewed beer as naturally as they baked bread. In recent centuries though, old-fashioned norms and industrialisation have turned women away from being the brewers of beer.” According to beer archaeologist Patrick McGovern, fermentation – the process that turns sugars into alcohol – lies at the foundation of human civilisation. “For as long as we have existed, humans have brewed alcohol. Alcohol cured infections, was used as pain relief, and was nourishment. For a good part of history, fermented beverages were safer to drink than water,” says McGovern.

The earliest evidence of brewing dates back to 7000 BCE in the neolithic settlement of Jiahu, China. McGovern’s team says it was a mixture of honey mead, wine and beer, and it was likely made by women chewing rice grains and spitting them in communal vessels ready for fermentation. In some regions of Japan and Taiwan, this traditional way of brewing is still part of wedding celebrations. “First beers were chew-and-spit-kind of beers,” explains McGovern. “Chewed mouth-sized masses of natural products – whether a fungus, fruit, grain, or tuber – is likely the earliest means by which humans extracted the necessary sugars for fermentation.” Human saliva contains an enzyme that transforms larger molecules into fermentable simple sugars – doing the same job as modern sprouting and malting processes.

Historical evidence shows that fermented beverages were made from barley in ancient Mesopotamia over 10,000 years ago. The Sumerians, one of the earliest civilisations in the region, would call on goddess Ninkasi to assist them in the brewing process. “Ninkasi, it is you who hold with both hands the great sweetwort, brewing it with honey and wine,” says their hymn to the goddess. Sumerian beer was believed to be a gift from the goddess to help them preserve peace and harmony within society.

In Babylonia, women enjoyed a relatively high degree of autonomy and were allowed to own property and businesses. They were both the producers and traders of beer. In the Code of Hammurabi – one of the oldest and best-preserved law codes – beer is mentioned in three separate laws. In all of them, the brewer is a “she”. Ancient Egyptians, who probably inherited their knowledge of beer from the Sumerians and Babylonians, worshipped goddess Hathor as the inventor of brewing. They even had a festival to celebrate her “drunkenness”.

Around the same time, in Mesoamerica, women would sit in circles chewing kernels of maize – the most available starch in the region – and use it to brew chicha, a fermented beverage that today is still consumed by indigenous communities across the Andes. Alan Eames, beer anthropologists, reported from the region around the early 1990s: “I asked them: ‘Do men ever make chicha?’ My question was met with gales of laughter. The women howled. Bent over in hilarity, one replied, ‘Men can’t brew. Chicha made by men would only make gas in the belly. You are a funny man! Beer is women’s work’”.

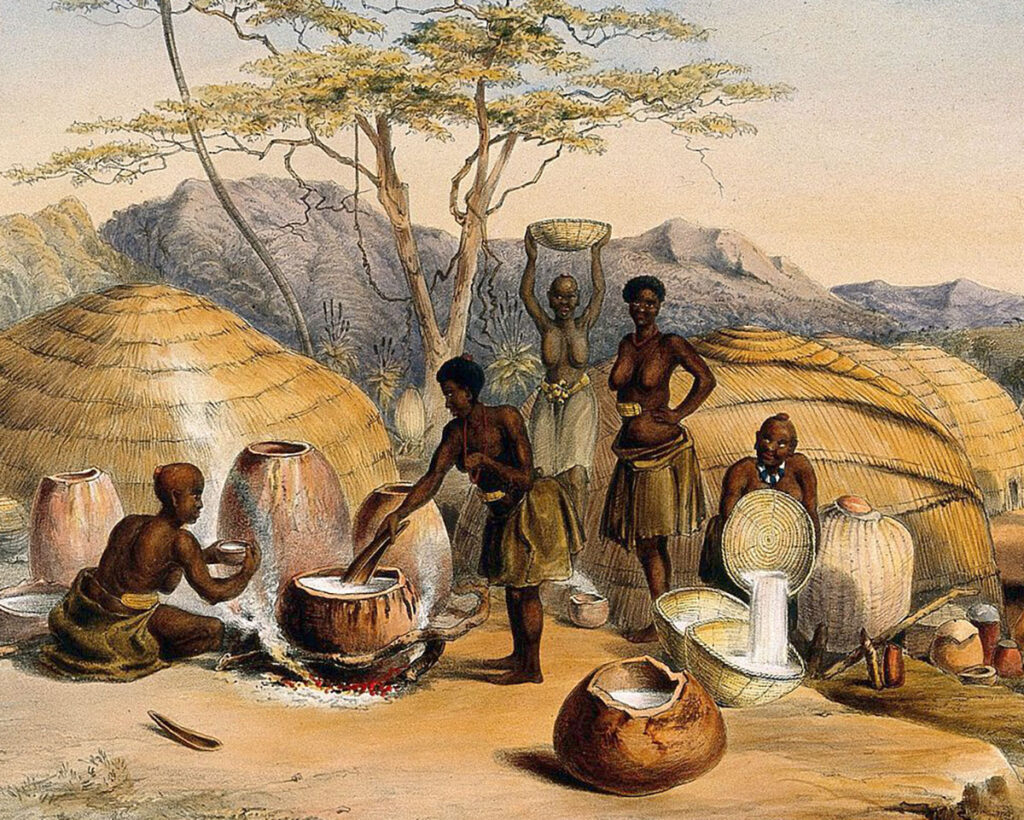

From the Wari’ in Amazonia to the Zulu in Southern Africa, from pre-Viking Scandinavians to Roman-times Germanic people and Siberian natives, historical accounts reveal that women have always been brewers. And the consumption of alcohol – an important social and spiritual activity – was protected by female goddesses and deities. “Ancient fermented beverages were no ordinary drinks, but had significant social functions,” says McGovern. As the makers of beer and owners of taverns, it is no wonder that, in these societies, women were held in such high esteem.

In 14th century England and medieval Europe, brewsters and alewives used to brew beer for their families and, sometimes, sell it in local markets. In England, alewives were also the tasters of un-hopped traditional ales – they used to taste it and set the market price. This was until industrialisation began and beer making became profitable. “When money got involved, men increasingly started brewing,” writes Gregg Smith, author of Beer in America, The Early Years: 1587-1840.

As colonisation progressed, the masculinisation and industrialisation of the brewing industry was exported to colonial settlements – although it is important to remember that indigenous communities worldwide are still resisting the change and in some of these societies, women keep brewing. During the Black Death, water became unsafe to drink and people turned to low-alcohol ales for hydration. During the same years, soldiers in the Hundred Years’ War were provided with a ration of six pints a day. Beer demand spiked and production went large-scale. Around the 16th century, men had replaced women in these pre-industrial establishments.

In her book Ale, Beer, and Brewsters in England: Women’s Work in a Changing World, Judith Bennet notices that the transformation of the beer industry was not brought about by technological advances alone. In fact, during those years, a new kind of society was born – a patriarchal capitalistic society where married women had no legal rights to propriety and where gendered divisions of labour were even more pronounced than before. Women did not stop brewing at the end of the 16th century; they hid in the forests, with cats to keep mice away and protect their grains, or kept brewing at home for their families. However, towards the end of the Middle Ages, brewsters started facing the opposition of the Catholic Church, who would blame them for men’s drunkenness and sins. Their knowledge of herbs and plants soon started to be negatively associated with witches, pointy hats and cauldrons. Witch trials during this age fuelled negative stereotypes about brewsters, meaning that women were removed from the industry.

The history of beer is a history of power and capital. While indigenous women from the Andes to Siberia, Eastern to Southern Africa have preserved traditional ways of brewing beers from maize, figs, millet or sorghum, colonisation and the invasion of their lands has meant that they now have less control over natural resources. Simultaneously, the emergence of larger breweries and corporations means that European and North American brands today dominate the industry.

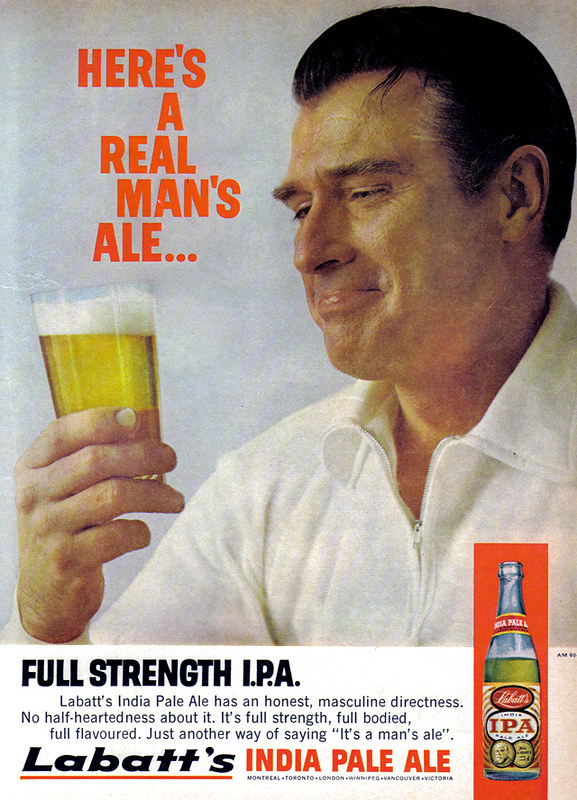

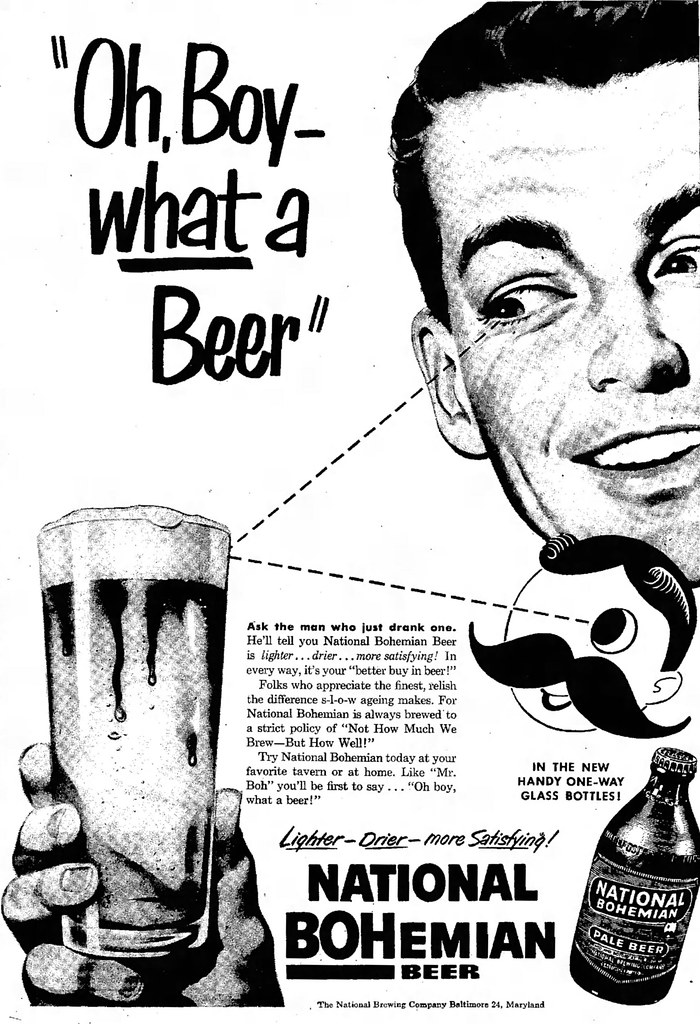

In the 1980s, the craft beer boom in post-prohibitionism America saw an emergence of new small, independent craft breweries and the desire to go back to traditional ways of making beer. But women are still fighting their way back to the brewery. With the craft beer boom, in fact, the misogynistic idea that “women can’t brew beer” re-emerged, together with sexist beer labels and ads suggesting “beer is a lad thing”.

A Stanford University study from 2019 found that both women and men in the US would pay more and expect better quality from a beer if it is brewed by a man. In 2007, Teri Fahrendorf founded the Pink Boots Society to support young women and non-binary people in beer. In a statement, Fahrendof said: “I quit my job after 19 years as a brewmasters and went in search of adventure. What I found were many new or young women brewers who had never met a woman brewsmaster, and in fact had never met another woman brewer.” Fahrendorf wanted to have a place for women brewers to unite and an archive of their successes within the industry, but there’s a long way to go.

In a world where beer is, to this day, the third most consumed beverage, it is easy to see how women’s exclusion from the industry goes hand in hand with the systemic oppression of marginalised groups. For many beer lovers, telling this story is a way to challenge the naturalisation of men’s position within the industry. Also, the belief that men are brewers because of their inherent predisposition to brewing and consuming alcohol. To reclaim a narrative is to reclaim a space. Women’s long history of brewing definitely deserves more space.

Read More