My mother was particularly generous on Sundays. She didn’t walk into our room and furiously pull the blankets off of us, she didn’t draw the curtains so that the hot summer sun would burn our bodies and she didn’t switch off the fan, leaving us to sweat. On Sundays, my younger sister and I were allowed to sleep until late in the afternoon. Until two, even.

When we did wake up, wafts of steam – pregnant with mustard, tamarind, curry leaves, cumin and asafoetida – would escape from the kitchen and into our bedroom through the slit under the door. Quickly, we would brush our teeth, our stomachs grumbling from having missed breakfast, and bob around my mother in the kitchen to watch her conjure her Sunday special: Sindhi Kadhi.

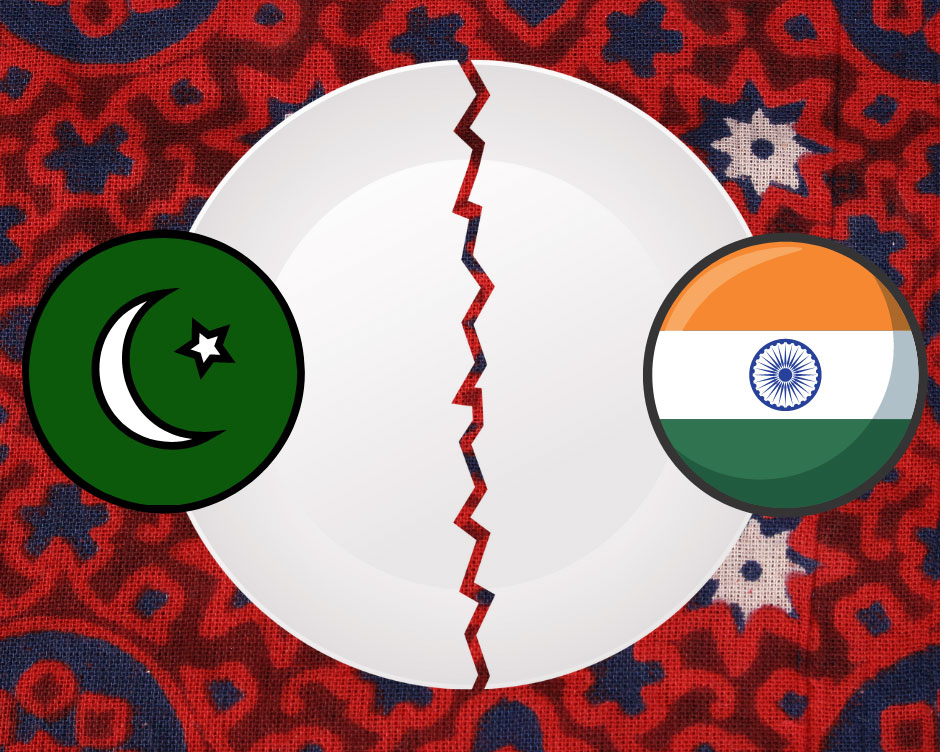

I come from a Partition family, which means that my parents and grandparents were displaced when India gained freedom from British rule in 1947, and the new Islamic-majority country of Pakistan was born. An arbitrary border was drawn across the map of colonial India by the British lawyer Cyril Radcliffe. This line, known as the Radcliffe Line, cut through the states of Punjab in the west and Bengal in the east. Muslims from India migrated across the border to Pakistan, while Hindus from Pakistan resettled in India. Even though the Punjabi and Bengali communities were no longer in their country, they were still tied to their land. The province of Sind, in present day Pakistan, was not divided and the region fell entirely under Pakistani territory. As a result, Hindus from Sind who migrated to India (more than 90% of the community fled) no longer had access to their homeland.

Sindhis in India, who were initially resettled in refugee camps, slowly started assimilating with people in local communities in different parts of India. They started life from scratch, which involved starting businesses, earning a livelihood and occupying homes. They were not only seen as “invaders” but were also not considered “Hindu enough” – even though religion was the very basis on which they were forced to migrate to India. This was because Sindhi Hindus didn’t follow traditions and practices that Hindus from other ethnicities in India did. Religion for Sindhis was, and still is, syncretic; combining practices from Hinduism, Sikhism, Islam, and Sufism.

This is because before the British colonised India, the region of Sind had been ruled by Muslims for 11 consecutive centuries. Sikhism, the tenets of which were formed by Guru Nanak’s teachings, originated in neighbouring Punjab and was adopted by Hindus in Sind. The influence of Sufism can be attributed to being part of the land itself, for Sind has been the home of mystics and pīrs for centuries. It is the land of Sufis. Sindhis in India went to the gurdwara as opposed to the Hindu temple. They ate meat; invoked “Allah” instead of “Ram”, a Hindu god; they didn’t wear the sari and never donned the bindi, for which they were considered “quasi-Muslim”. In order to assimilate with the local communities, Sindhis slowly began to shed their cultural identity. Many became vegetarian, others started praying at temples and nearly everyone started wearing saris in order to be accepted; not othered.

Among the few things that Sindhis brought with them during Partition, food was one. Sindhi Kadhi, which my mother makes so lovingly on Sundays, is my favourite dish in the world. Typically, it’s a thick-ish curry made of gram flour, tamarind, cumin, curry leaves, asafoetida and other Indian spices, to which several vegetables (including potatoes, okra, carrots and lotus stem) are added. My sister loves okra and I love potatoes, so my mother only added these two vegetables. Sindhi Kadhi is a staple for lunch on Sundays, when, in my home, the responsibilities of life cede slightly into the background. The dish is also made on Sundays in many Sindhi households because it’s more tedious to cook than a regular curry; you must stand at the hob, stirring, for a long time, so the gram flour is evenly mixed.

Eaten with plain steamed rice, a nap is the ideal post-lunch activity, simply because the kadhi (curry) is so heavy that no serious work can be done. This is a dish that allowed, perhaps even forced, my mother to spoil us silly, even if she didn’t want to. It’s not only the flavours in this simple-yet-complex dish that makes it my favourite, but also the memories of my mother cooking it; always fussing about the countless ingredients to be added at an exact time and trying to shoo us out of the kitchen. This memory makes it particularly precious.

Every state in India, or even different places within a state, have their own cuisine. Gujaratis, for instance, add jaggery or sugar to their kadhi. Malayalis, from the southern Indian state of Kerala, make their curry with coconut milk. In India, there are a hundred different ways to make just the humble curry, let alone other sabzis and meat. There are different ways to make paratha, parotta, naan and thepla, and Sindhis make the koki, a flatbread that can be eaten with daal or just yoghurt and pickle. My mother’s Sai koki, a coriander-based flatbread, is my favourite breakfast item. She has promised to make 50 of them and send them over with my younger sister who is visiting later this month.

Sindhi food, in many ways, tells a story of migration. Partition is considered the biggest forced migration in the history of humankind. When a whole population was forced to migrate overnight in 1947, they held the intangible connections to their homeland close: folklore, religion, language, memories, stories and recipes. Gradually, the culture of the communities that adopted them seeped into the Sindhi community in different ways. In Bengal, Sindhis picked up the Bengali language, prayed to Kali and Saraswati – goddesses that Bengali Hindus prayed to, and adopted local flavours into the Sindhi cuisine. Similar changes took place among the Sindhis of Bombay, in the state of Maharashtra. Sindhis who moved here picked up the Marathi language and started worshipping the god Ganesha. Even their food started featuring ingredients native to the region. Very soon, while the basis of Sindhi cuisine remained the same, some authentic Sindhi dishes were bastardised in a hundred different ways.

My mother, for instance, cooks Sai Bhaji – a gravy of lentil and spinach – in mustard oil; an ingredient Bengalis use heavily in their cuisine, instead of the sunflower oil that the original recipe demands. Panch phoron, which means “five spices” in Bangla, is a mix of cumin, fennel, nigella seeds, mustard and fenugreek – something my mother uses in nearly every Indian dish. It is practical, easily available and flavourful. When I visit my cousins in Bombay, the flavours in the sai bhaji that my aunt makes are ever-so-slightly different, even though, at the heart of it, the dish is very close to my mother’s. So, everybody’s version is ‘authentic’, and everybody’s version is ‘improvised’.

For me, my mother’s will always be the original. It has been nearly nine months since I tasted her food. I couldn’t cook like her if I tried, so, I have raised the white flag here in London prematurely. But London is where, for the first time in my life, I met a Sindhi from the ‘enemy state’: Pakistan. As an Indian citizen, it is near-impossible for me to travel across the border. Pakistanis, similarly, cannot enter India. This is a consequence of Partition and three wars fought between the two countries.

In September, I was invited by the Commonwealth Scholarship Commission (on whose generous grant I am pursuing my Master’s in the UK) to attend a summit where we could meet and interact with scholars from other Commonwealth countries. I was assigned to a table where there were two Bangladeshis and three Pakistanis. Of those three Pakistanis, one turned out to be a Sindhi. Oh, the joy! I looked at her and immediately had a feeling that we had a shared ethnic background: slight build, sharp nose, big-ish sunken eyes. Her name is Amber (pronounced Um-ber), meaning sky. My name is Chandni, meaning moonlight. She could have been me. Or I her.

We connected instantly, conversing comfortably in Sindhi and cracking a few silly jokes. They were all the same, even though we didn’t share a land. How the hell could our jokes be the same? I was amazed; there’s no better way to describe it.

I asked her what her favourite Sindhi dish was. Chicken Karahi, she responded. I told her my favourites were Sindhi curry and koki. “What’s koki?” She asked. “You don’t know koki? What about lola? Do you like lola?” (Lola is a kind of thick paratha made with whole wheat flour, sugar, jaggery and ghee) She started laughing harder. I thought: what is this woman smoking? Is she really Sindhi? She asked me earnestly whether these are really names of dishes. I told her they are, asking what she eats at home in Karachi. Biryani, gosht kebab, nihari, haleem and korma, she says.

All these are common to most of South Asian cuisine, I say. What are the Sindhi dishes you eat at home? She looks confused. I start listing the dishes my mother cooks and, out of these, she recognises only two. Sai bhaji and dal pakwan (crunchy fried bread eaten with lentils for breakfast). While her mother cooks the former at home, the latter is devoured at restaurants. In India, one would be hard-pressed to find any Sindhi food outside Sindhi homes. In an instant, Amber becomes distant to me. How can we be from the very same land and our food be so different? So much so that she hasn’t even heard of these dishes.

I realise that our disconnect is a consequence of Partition. When Hindus from Sind migrated to India, Muslims from all over India moved to Pakistan – many of whom were from villages, but now wanted to live in Karachi, a big port city. These Muslims from India migrated from different states; from the central Indian state of Uttar Pradesh and eastern Indian state of Bihar to Gujarat in the west, and Hyderabad down south. Over the years, Punjabi Muslims, Afghans, and Balochis settled in Karachi, too. Slowly, cultures from different ethnicities overlapped to form a mixed, cosmopolitan kind of cuisine. Today, more people speak Urdu, Punjabi and Pashto in Sind than they speak Sindhi. Another interesting factor is religion. Food in Karachi is heavily influenced by Islamic cuisine from central and south Asian communities, and mostly involves meat. Sindhis in India enjoy meat dishes like the mutton teevarn (a Sindhi lamb curry) or the Sindhi pallo (hilsa fish cooked in an onion-tomato gravy), but vegetarian food is an important part of our diet.

While Sindhis in Pakistan enjoy the privilege of living on their homeland, the food is arguably inauthentic. On the other hand, Sindhis in India can only dream of visiting their homeland, let alone living on it. Yet they hold Sindhi recipes close to their heart. There is no point thinking about which is a better deal. But what all this means is that, while food unites most communities in the world, Sindhis on either side of the Radcliffe Line don’t quite see eye-to-eye. We may share emotions when it comes to Partition, politics, war and even language, but unfortunately food is not what unifies us.

Last week, I met Amber for a meal at an Indian-Pakistani restaurant and we talked about Alphonso mangoes; a special mango cultivated in the western Indian state of Maharashtra that I was so excited about finding in London. I asked her if she had ever tried them. She said no, but asked if I had ever tried the Sindhri, another special kind of mango grown in Sind; one my mother has talked about all her life. I have wanted to try it since the first time I heard about it. Amber’s cousin from Pakistan is visiting London in a couple of weeks with a carton full of them. I plan to meet Amber to give her an Alphonso in exchange for a Sindhri. Hopefully, there will be resolution.

Read More: