Artist Kasia Grzelak discusses her new series ‘Matka Poltka, Imigrantka’, the Catholic Church and her love of bread and salt

If you have taken the metro in Newcastle recently, chances are you have seen some of Kasia Grzelak’s artworks from her latest “Matka, Polka, Imigrantka” series (Mother, Pole, Immigrant). They were meant to be displayed at the BALTIC Centre for Contemporary Art, Gateshead last year, but the pandemic meant that they ended up as prints on public transport. Now, Grzelak – who identifies as “Whitley Bay’s only Pole” – is looking forward to her work being seen in the flesh again, as BALTIC prepares to re-open its doors to visitors.

Looking at Grzelak’s art, it’s not hard to guess that she thinks about food a lot. Her latest series includes two intimate portraits of barszcz, the classic beetroot stew. “Spending Christmas with family can be a mixed bag,” she says from her seaside studio in Tyneside, “but barszcz is the one dish everyone looks forward to. And whenever I would have barszcz I would look deeply into it – and you really can take a deep look into barszcz, it’s just this rich crimson which engulfs all the porcelain – and I’d think ‘oh barszcz, you’re always here for me in these times.’ ”

That’s why she ended up painting the soup twice, once in ink, the other in oil paint, but she doesn’t feel done with the dish yet. “Really, I think I might do a whole series on barszcz. There’s just something about beetroot, I guess it literally is a root vegetable,” she laughs.

The roots of “Matka, Polka, Immigrantka”, however, were initially less culinary. The series was meant to consist of portraits of first and second generation Polish women in the North of England, but it soon turned introspective. “I ended up interrogating my own memories instead,” Grzelak says in-between sips of tea, “memories and photos of weddings, barbecues – just places where you would have fun, eat loads of food, drink.”

For the young artist who grew up in the diaspora in Cumbria, personal gatherings and celebrations were cultural events. “A lot of knowledge was passed down through food and drinks,” Grzelak explains, “Gatherings with families, backyard barbecues – that’s when we would learn. Sharing stories, sharing knowledge of our national identity, our history, it happened within those spaces.”

But for Grzelak the quintessential Polish food is not the barszcz, the bigos (Polish Hunter stew), the pierogi (stuffed dumplings), or even kiełbasa (meat sausage), but “bread and butter and salt” – the food that only started tasting Polish to her once she left Poland.

“When the first polski shop opened and mum came back with a loaf of bread and polski butter, we sat around her like poor beggar children, asking for more

“When I first saw the bread after we moved here, I was so disappointed. The white square – it looked just like a piece of paper!” Grzelak recalls, the outrage still fresh in her voice. “When the first polski shop opened and mum came back with a loaf of bread and polski butter, we sat around her like poor beggar children, asking for more.”

Grzelak’s family immigrated in the early 2000s when Polish delis were still a rarity in the UK and certainly in the North West. “The only things we bought with us to England were our clothes, an old radio, and my mum’s notebooks where she copied out recipes from my grandma’s notebook,” Grzelak recalls, “but when we first arrived, our parents actually tried to anglicise us, we had shepherd’s pie and roast meat with chips. We only started having gołąbki [stuffed cabbage leaves] and bigos later.”

After Grzelak moved from the west coast to study fine art at the University of Newcastle, away from her Polish parents, their Polish cable televisions, and their hometown’s close-knit Polish community, cooking became more important. “I live in Whitley Bay now, which is mostly English pensioners, and I find I cook more Polish food than ever before,” she says, “It’s a way I can identify with my own nationality that brings me joy, as well.”

Other joyful aspects of Polishness are harder to come by, she explains. From what she calls the “tyranny of the Catholic Church” to the “intergenerational trauma” that can be traced back to “the partition era, probably,” Poles, according to Grzelak, are plagued by self-perpetuating neurosis.

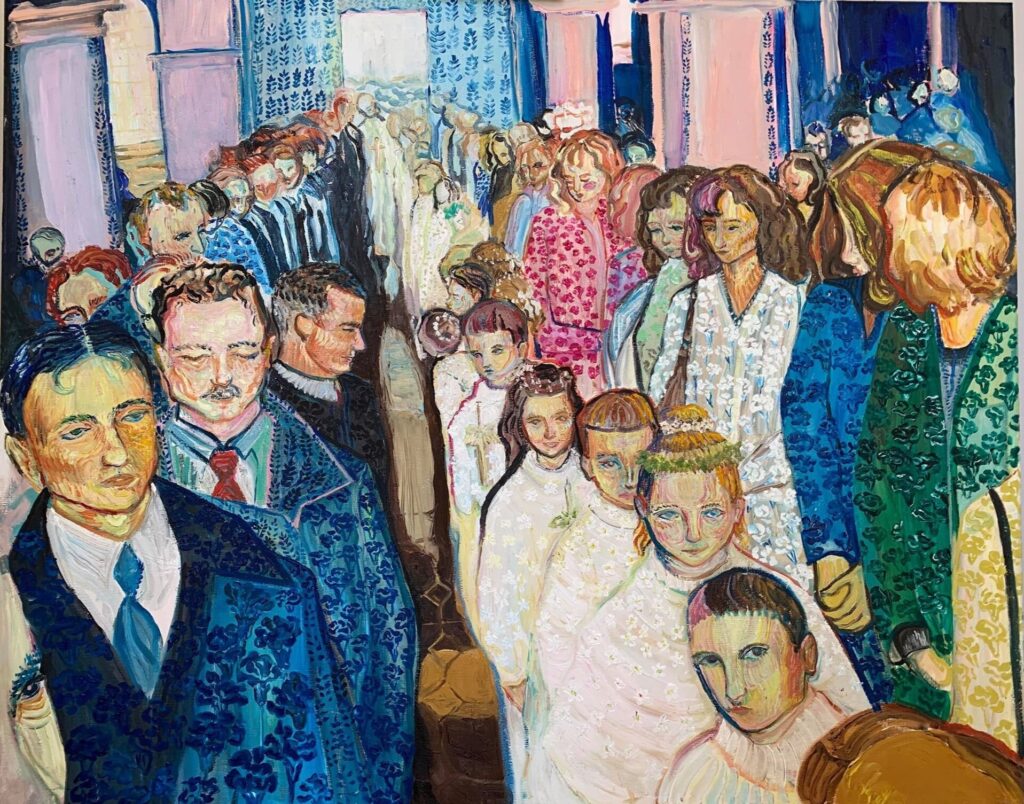

“Many of the paintings in the series are placed in churches or focus on sacraments. They’re joyful events, yes, but there is an ambiguity there – fear,” she says. Her works Polish Mass and First Holy Communion have both recently been displayed in The Holy Art gallery in Hackney during an exhibition tellingly titled, “Nostalgia”, and are heavily peppered with motifs of carnation flowers. “My parents always said that carnations are communist flowers – for no particular reason it’s just an association they have,” she says. For Grzelak, who was born well into the new capitalist order, communism is a ghost that lurks, buried deep in the Polish mentality. “It’s that scarcity anxiety,” she explains, “that left over fear that food will run out, somehow. I think that’s mostly what I understand when I say ‘communism.’ ”

“The series has been very therapeutic for me,” Grzelak says, “it helped more than any actual therapy I did.” She pauses, “First Holy Communion is my favourite, it makes me cry. It’s from my sister’s communion, the last sacrament we had in Poland. She looks so innocent there, and she has been through so much now, because of immigration.”

Currently, Grzelak is planning to qualify as an art therapist. Part of the requirement, she explains, is one year’s employment in the care sector. For over two months now she has been working three days a week in a care home for adults with disabilities. “I see my job as a care assistant as a way of living and learning about people, maybe even just practising art with people with disabilities,” Grzelak says. So far, she has organised one workshop in Whitley Bay and has been doing commissions for the care-home residents. “We painted a portrait of Elvis Presley for one resident, he keeps it in his room. Next we’ll be working on a landscape,” she smiles and turns her camera to a prepped canvas.

As for the “Matka, Polka, Immigrantka” series, Grzelak is not satisfied. “I feel like the project isn’t even complete,” she says. “I want to know how it progresses when I start studying art therapy, how it will evolve from that.”