People from different background across the UK talk about their experiences of funeral food

Today, British grief is not solely defined by square-cut sandwiches, says Callsuma Ali, host of the “Bereavement Room” podcast, which centres on highlighting underrepresented voices: “It’s not the British Asian experience. I like a sandwich as much as the next person – I love Birleys! But there wasn’t one single sandwich in my dad’s, mum’s, or my brother’s funeral.”

When Callsuma’s father passed away in January 2020, the family held a farewell lunch. “My sister put out this massive meal, and my brother-in-law and I helped her out. We all sat on the floor with cushions and a huge table of food. It was a very nice way to say farewell to dad.” Farewell meals are hugely important to the Bengali community. “[They] are seen as a form of remembrance and prayer for the departed souls into the next world,” says Callsuma.

British funeral food today is complex; like British identity itself, it can’t be compartmentalised. Everyone follows their own traditions and grieving process and there are a diverse range of foods that accompany this. What does seem to ring true in all British experiences of funerals though, is that the food always plays a big part.

The lunch started with some light snacks, says Callsuma, “We had these rice flour snacks called Nunor Bora with lots of different chutneys, as well as Handesh, which is a [similar] snack that is deep fried in molasses.” After this came the main dishes like Aknhi Fulab, “It’s yellow rice, which you can have with vegetables, or a choice of meat, chicken or lamb,” says Callsuma. Other plates included a Bengali fish fry with onions and a prawn curry with potatoes: “Seafood is [the Bengali] national dish, so it’s a big part of our diet.”

But it wasn’t only friends and family from the Bangladeshi community at the lunch: “Because there were people from across the South Asian diaspora attending, it was quite a varied meal that was offered on the day. There were some who were Pakistani, Indian and English. If someone [didn’t] want something, there was an alternative. There were also a few veggie dishes like Samosas and Spinach Bhaji, eaten with rice.”

The food given in Bengali communities following a major loss is “second to none” and brings comfort through intense moments of grief, says Callsuma. Following the loss of her mother ten years ago, local restaurants stepped in to support her family: “They gave us these pans of food, and I’m not talking about the small pans that we have in our kitchens nowadays, but the huge ones they use in Asian restaurants. When I saw that, I thought, my God, how generous, how kind. For me, [food] brought a sense of culture, community and solace. It does console us in hard times.”

‘The food given in Bengali communities following a major loss is ‘second to none’ and brings comfort through intense moments of grief, says Callsuma’

Christopher Stephenson, co-founder of Christopher’s Caterers based in Bexleyheath, also sees food playing an important role at funerals. With his parents being Jamaican, Christopher’s catering service is inspired by the food he grew up with at West-Indian events in Britain. “A funeral [for West-Indian communities] is an all-day event,” he says.

“We’d normally get some soup and with that what we call hard dough bread. Then people would sit down, say a few words about the deceased, and then we would eat. One of the most popular dishes that you’d find at a funeral [we cater at] is curry goat, jerk chicken and curry chicken, with some plain rice and peas.”

For Christopher, food is a vital element at a funeral: “Everybody loves to eat, and especially with West Indian funerals, you eat, and you come and reminisce with that person, with friends.” But there’ll always be a lot more on offer at a West-Indian event, due to the sheer numbers attending: “You don’t have to be invited. If you knew that person, you just turn up. We never know, 100 people might come. The last proper funeral I catered for was 400 [last March], That’s the last time I’m going to do anything like that!”

‘There’ll always be a lot more on offer at a West-Indian event, due to the sheer numbers attending: “You don’t have to be invited. If you knew that person, you just turn up. We never know, 100 people might come’

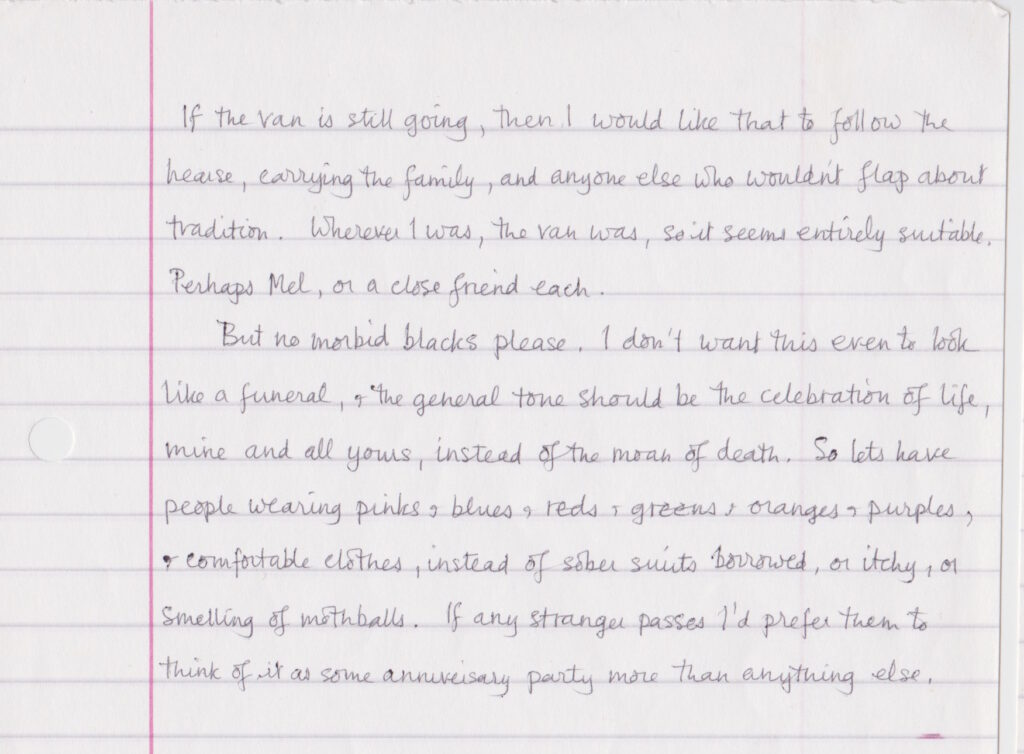

Food was also key at funerals for Ellie Harrison, 37, artistic director of The Grief Series, an artistic collective working with topics surrounding bereavement, based in Leeds. At the age of 17, Ellie lost her mum Maggie and was faced with organising her first funeral with her sister. There was a three-week period between Maggie receiving a terminal diagnosis and her death. “But she did have a bit of time to write down instructions and a plan for the funeral which was a real help,” says Ellie.

Ellie treasures these impeccably neat handwritten notes. In them, her mum emphasises the importance of food: “Make sure there are one or two substantial dishes for people who have come a long way or who would be naturally hungry. Canopés aren’t always enough on these occasions.”

At the funeral the main meal was hardly dainty or good-looking on a buffet table. It was “a big vat of stew, with bread,” says Ellie. She describes how her mum’s dishes were inspired by wartime thinking: “In all of her own recipes she talks about how you can bulk up a meal to feed 12 if you need to, if you don’t have enough bacon, just put more potatoes in. It’s got this strange war-time values set. The idea that you might not have access to money or ingredients, and that you might be trying to feed more people than you expect […] I think the funeral food, although not beautiful or sexy, was an extension of her.”

During the pandemic most couldn’t have the send-off they deserved, but for Polly Langford, 44, a children’s bereavement counsellor from Cornwall food was still crucial. At her friend’s father’s funeral in December last year, they gave out £10 fish and chip vouchers to those who couldn’t attend due to event restrictions : “This was his favourite food. It offered people a moment to just sit back and reflect and remember their dad. It was important, particularly given Covid, to help his friends just feel that they could do something and be able to say goodbye in another way.”

At the funeral itself, Polly says that the food acted as a reminder of his identity: “He’s very much a Cornish man. It was always his wish to have Cornish pasties and saffron cake, which is something that’s quite common here. It just feels like [the food] helps connect them back to where they’ve come from.”

Across cultures, different dishes play the biggest of roles at funerals. They’re a means for remembering that person you’ve lost, they bring people together and help people begin to process the life-changing journey that is grief.