Welcome to Gretel’s Bookshelf, where we spotlight interesting cookbooks from around the world, speak to experts about their history, and pick out the best recipes.

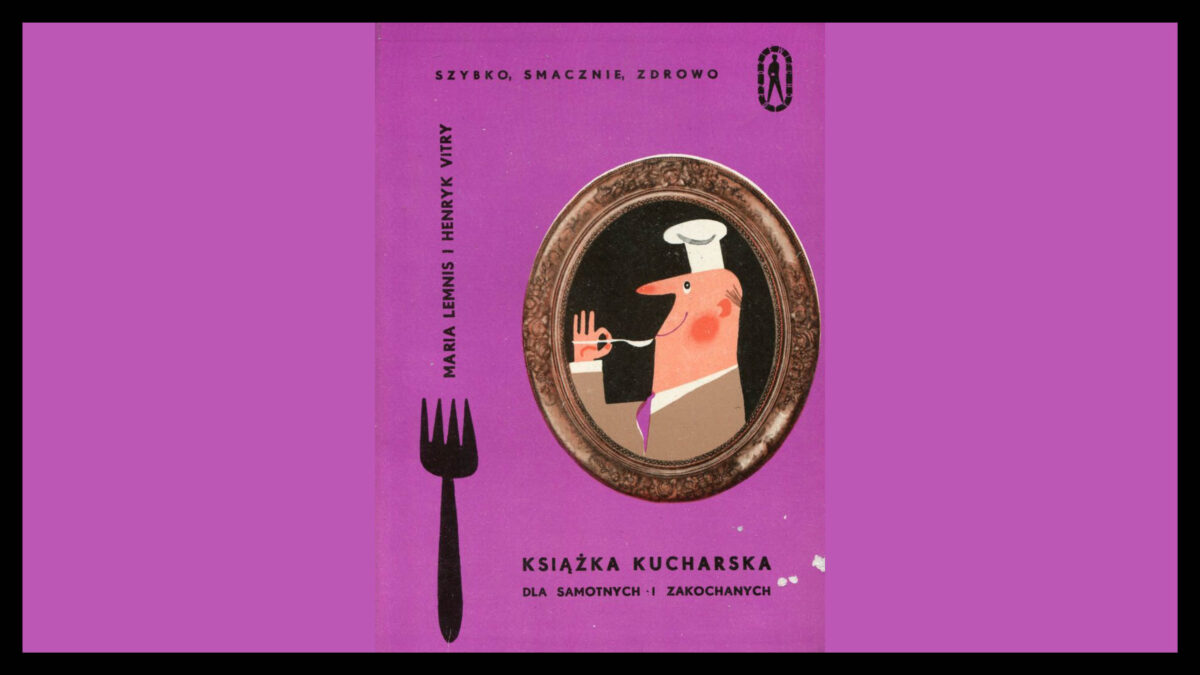

Not many people remember Tadeusz Żakiej, a post-war Polish musicologist and composer who is at most a footnote in the history of Polish theatre and performance. Meanwhile, Żakiej’s contemporaries, a married couple of culinary enthusiasts, Maria Lemnis and Henryk Vitry, still enjoy a small but appreciative circle of admirers who swear by their recipes. Lemnis’ and Vitry’s Cookbook for those who are alone and those in love*, a manual aimed at kitchen-shy single young men, remains a crowd-pleaser half a century after publication.

What do the friendly, blissfully domesticated couple, who co-authored cookbooks and countless culinary articles, have in common with a cosmopolitan confirmed-bachelor musician? At first glance, nothing, which is precisely the point. Because Lemnis and Vitry are in fact Żakiej’s inventions.

Żakiej was gay at a time when homosexuality was tolerated (at best) among the artistic elites of Warsaw and actively condemned by the party both in Poland and in Moscow. Meanwhile cooking – for all the “emancipatory” efforts of the communist regime, which sought to push women into both productive and reproductive labour – was still firmly in the feminine domain. Thus Żakiej, who was well respected both for his music and his academic research, kept his passion for cooking as concealed as his sexuality.

Today his cookbook for single men is a time capsule of gradually changing domestic mores and gender roles: “Everybody among us likes to eat well and to one’s heart’s content,” the fictional couple assure their reader as he takes his first steps in the kitchen, “both the ‘fair sex’ and the ‘worldly gentlemen.’”

It hit Polish book shops in 1958 – a year before Polish secret services expelled the French philosopher Michel Foucault from the country (bet you didn’t know he used to live in Warsaw) for being too gay – and it captures social transformation which started to take place in the Polish People’s Republic as the country slowly recovered from the war.

“Cookbooks often tell you about the world outside of the kitchen,” says Fabio Parasecoli, Professor of Food Studies at New York University, who researched Żakiej, “they show how people imagine themselves. What they think they are supposed to do due to their role, or what they would like to do.”

It shows the life of people that happen to live in a place where maybe you have to line up to get food, but it doesn’t feel like communism was the inspiration.

According to Parasecoli, the life of the single white-collar male presented in Żakiej’s cookbook is mostly aspirational, a socialist version of the “bourgeois good life.”

“It doesn’t feel like a communist cookbook,” Parasecoli says, “It shows the life of people that happen to live in a place where maybe you have to line up to get food, but it doesn’t feel like communism was the inspiration.” However, the book’s fictional authors do seem anxious to pre-emptively deny accusations of bourgeois gluttony, “Food is not just a sad necessity, it can also be pleasure,” they coax their hard-headed reader, “a pleasure that is available to us…three times a day.”

While cookbooks for men were hardly unheard of and can be found all around the world, especially in late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Żakiej’s volume is unique in the way it addresses married life.

On the one hand Maria’s and Henryk’s marriage seems more egalitarian than was standard at the time. “It looks like the two of them were collaborating, learning together how to do things and learning how to entertain guests,” says Parasecoli, “in the introduction there is their story; how they met, when they got married, it’s very cute.” At the same time, Żakiej does not seem to be interested in rocking the boat of social conventions too hard. The book still presumes that its readers will not be bachelors for too long and marriage is presented as the natural long-term solution to their cooking inaptitude.

*the Polish title is Książka kucharska dla samotnych i zakochanych and it was last reprinted in 1992 by the magazine Twój Styl.

“Maria Lemnis’” and “Henryk Vitry’s” recipe: Pork cutlet “au naturel” with applesauce

Time: 20 min

Cost: £

Serves: 1

Difficulty: Moderate

Equipment:

- A small saucepan

- A frying pan

- Tenderiser/ meat mallet (optional)

Ingredients:

- 100g – 120g pork loin chop (not too fatty)

- A dash of salt

- A dash of pepper

- Oil

Method:

Apple sauce

Peel a cooking apple and remove the seeds and core. Dice it.

Place the chopped apple in a small saucepan with 4 tablespoons of water. Simmer on medium low heat with the lid on for 5 minutes.

When the apple has softened, mash it with a fork with a dash of salt and pepper.

Cutlet

Place a 100g – 120g slice of pork loin on a chopping board and give it a good tap with the knife handle (or a meat tenderiser.) Gently rub in salt.

Heat 2 tablespoons of oil on a frying pan until burning hot.

Stick the schnitzel on the pan and fry it on both sides for 5 minutes.

Place the schnitzel on a dish and pour the applesauce on top

Gretel’s Tip: For an extra hearty meal serve up with a side of crushed boiled potatoes with a healthy dollop of butter and salt.