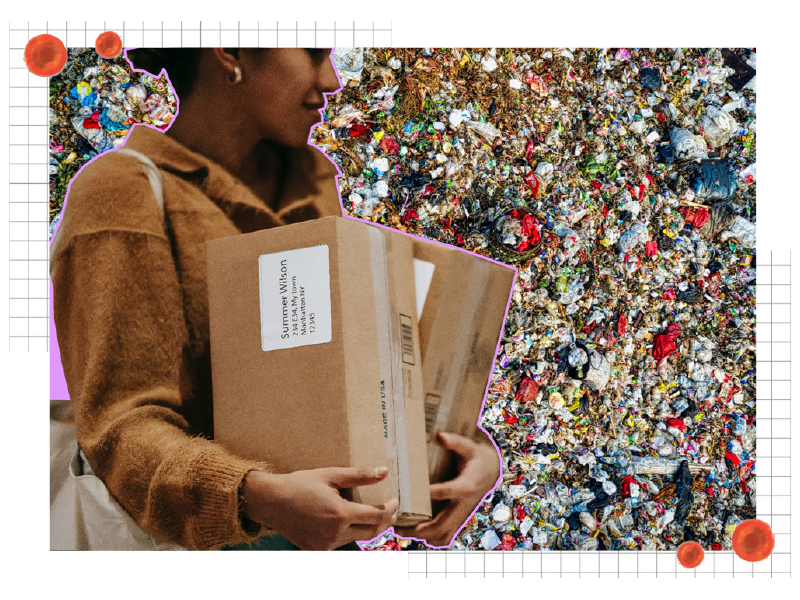

When was the last time you ordered something online in multiple sizes, or extra items to get free delivery, knowing full well you’d return at least some of it?

It’s something many of us are guilty of. With free returns, QR codes and drop-off points, it’s easier than ever to return unwanted items and many of us will deliberately overorder as a result. Because of this, online returns are due to rise to £5.6bn by 2023, with fashion and footwear as the main drivers, a 2018 study by GlobalData has found.

So what really happens when you send off that H&M parcel to be returned? Dr Sharon Cullinane, Professor of Sustainable Logistics at the University of Gothenburg Business School in Sweden, explains that returned clothes frequently take “long, convoluted journeys” before they actually get back to the company.

Returns are often sent to eastern European countries where the wage costs are much lower

“Often, they get sent to European countries such as Estonia or Poland, where the wage costs are much lower. The checking process of a return has to be done manually and takes quite a lot of labour, so fashion companies do anything they can to reduce costs. Basically, they’re substituting cheaper labour for increased transportation costs, but it’s worth it for them financially. It takes three times longer and costs three times more to process a return than it does an outward delivery.” If the item was bought from China it will often go back there before it is actually put back on the shelves or into the warehousing system. Even if a returned item stays within the country, it will go on a few journeys.

It’s a different story with in-store returns, where most will stay within the store and some may be transported to a different branch. When an item returned in-store isn’t in a resalable condition, Cullinane said what happens to the faulty items will “depend on the company’s policies.” They might get sent directly to charity, or they might get sent to a landfill. “Companies don’t want to send things to landfill,” Cullinane said, because it costs them money to do so, and they don’t get anything in return.

However, there have been instances in the past of high-end brands destroying their stock in order to protect their brands. Burberry revealed in 2018 it had destroyed millions of pounds worth of unsold clothes in order to protect their value, so they wouldn’t go on to be sold cheaply secondhand. Part of the problem is, as Dr Cullinane explained, brands do not have to disclose what they do with returns. “Nobody wants to talk to you. I think companies are a bit ashamed. They want to be as sustainable as possible, but they don’t know what to do with returns. Their primary focus is on sales, not dealing with returns sustainably.

Companies’ primary focus is on sales, not sustainability

“A few years ago, return rates were about 10%, and companies could deal with that without too much of an effect on profitability. Now, the return rates for evening dresses are about 80%.” The main reason people overorder is because they can’t gauge their size online. “It’s also very hard to gauge colours and materials online,” said Dr Cullinane.

But companies continue to put customer convenience ahead of environmental costs. Amazon recently launched Prime Wardrobe, where you can order up to six items and try them for seven days before you decide which ones to keep. You are only charged for the items you keep, with no delivery or return fees. It’s like an at-home changing room, at the cost of the planet. “It’s almost like they are encouraging you to buy things you don’t want,” said Dr Cullinane.

“Retailers are responsible, but customers also need to understand that there are environmental consequences of just putting things back in the post. When there’s no financial consequences to the buyer, it is likely that they are going to abuse free returns policies.”

Has Covid changed things? “The rate of returns has dropped slightly, maybe because people haven’t wanted to go out to the post office. Or because they’ve got more time and so they’re thinking more about what they’re buying,” Dr Cullinane said. “The kind of clothing items that have the highest rate of returns are evening dresses and fast fashion goods. People are buying less because they’re not going out. They also may not have the disposable income as well.”

It’s almost like they are encouraging you to buy things you don’t want

“Even after Covid, people will continue to buy more things online. I think return rates will continue to go up unless something is done to stop it.” If you assess the whole life cycle of a piece of clothing, the returns are probably a very small element. Things like growing cotton and the manufacturing process have a greater environmental cost. But as Cullinane said, “we can do something about returns.”

The major environmental cost of returns comes from the transportation of garments, as well as the resources and land used by the vast warehouses set up to deal with returns. For Dr Cullinane, more transparency is key. “The customer has to be educated about the impacts of returns, and companies need to improve their websites. A standard sizing guide across brands in the UK or Europe would be useful.”

“Sustainability is an environmental thing. But it’s also a social and economic thing. If we don’t buy things then we’re going to penalise countries where clothing manufacturing is a large part of their economy. We have to be careful with what we buy and not overbuy, but buy good quality things that last a bit longer. And just think before we buy things, do we actually want them and will we actually wear them?”

We asked 18 fast fashion brands what they do with their returns:

ARKET: “With faulty returns, we will try and recycle the material to make recycled clothes in order to reduce waste. This is if the material is in a usable condition. For regular returns, these items are washed, quality checked and then packaged in order to be sold again.

“We strongly believe in recycling and reducing waste as much as possible. We are a conscious brand and believe in creating a sustainable environment and have a minimal environmental impact. You can find out more about our returns and recycling here.” ARKET could not provide the percentage of faulty items they are able to recycle.

Missguided: “We want to do right by the people we work with and the environment we operate in and have signed up for the BRC – Better World initiative. You can read more about that commitment and the work we’ve done on product packaging, eco-friendly home laundry standards, and recycling of products at missguided.co.uk/csr.”

Primark: “At Primark, one of our key sustainability principles is to never shred or incinerate any product that is safe and usable. To reduce landfill, we donate unused clothes, shoes, accessories and homewares from our European stores to the children’s charity Newlife, which sorts and resells or recycles the goods to raise funds for disabled and terminally ill children and their families.

“Any returns that are not damaged or faulty will be put back on sale in-store. If an item of clothing is shop damaged (dust, dirt or marked) while on the sales floor, but is not faulty, we may mark it down at the point of sale with the customer. If faulty clothing is returned by a customer it will in most cases be sent to Newlife to be processed, however, if a wider issue is identified it will be returned to the manufacturer.”

H&M, COS and PrettyLittleThing refused to comment. Dorothy Perkins, Debenhams, Urban Outfitters, Anthropologie, Pull & Bear, and Other Stories, Zara, Miss Pap, Coast, Karen Millen, Nasty Gal and Boohoo did not reply to a request for comment.