A newly opened exhibition on the work of Peter Doig is one of the hottest talks of London. In a conversation with its curator, we took note of the best takeaways

When Peter Doig first moved to Trinidad, he wasn’t yet two years old. The early relocation from Edinburgh, his birthplace, marked the beginning of a series of moves that gradually turned his life into a roving collection of memories to handle with care.

Throughout his artistic production, photographs, songs and poems gathered on the road will repeatedly function as an inspirational source to set off emotions and fuel even Doig’s creative journey. Its trail can now be walked in an exhibition of paintings and etchings at The Courtauld Institute of Art in London open until May 29.

Doig’s visions, not surprisingly, would spawn the unequivocal environments of his growth. But, despite their lucent realism, a consistent feeling of dislocation can as well be perceived in his works, as if the undoubted influence of each setting is not to seize his flair completely.

“I never try to create real spaces – only painted spaces,” said Peter Doig in a remark stuck on a wall of the gallery. “That may be why there is never really any specific time or place in my paintings.”

By only passing through the days and spaces of his life, Doig uses colours and brush strokes to portray scenes that unwittingly solve a dialectical problem of our time. His art proves to what extent experiences affected his perception of things but also how their diversification, disclosed through the mystery and strangeness of the unexpected, let him slip away from a cultural and ideological crystallisation.

Doig spent part of his childhood and teenage years in Montreal, Canada, and returned to London to pursue his ambition to become a painter. Here, he gained the formal mastery that would steer and nurture his painting career with riveting models spanning from Classical Greek art to American modernism.

Over the following decade, Doig would secure an international reputation as one of the leading contemporary artists of his time. Yet, as his acclaim led to a Turner Prize nomination in 1994, he soon hushed the suspicion that fame could blur the lines between establishment and attachment settling back to Trinidad in 2002.

The time on the island had a similar unfolding. The richly diverse culture of the Caribbean inspired much of his production with music, poetry and images that would serve as initial imaginative traces to sketch multiple works. However, just before he could become fully accustomed to the Trinidadian surroundings, several wandering punctuations in Europe and America would juxtapose his stay with other beneficial encounters. These would even keep him distant from the fervour triggered by the mind-blogging auction of ‘Swamped’ (1991), sold at Christie’s for the record-breaking price of $39.9 million in 2021.

The culmination of his voyage was a comeback to where it all started. For nearly two years Doig has come to Britain again and has a studio in Bethnal Green where he’s managed to relentlessly complete works commenced in Trinidad and periodically retrieved in Switzerland and Germany just in time for the opening of the display.

“Quite interestingly, the larger of our two rooms that the exhibition is in is about the same size as the studio where he paints in London,” said Dr Barnaby Wright, Deputy Head of The Courtauld and Daniel Katz Curator of 20th Century Art, who conceived this show directly with Doig and spoke to Tablecloth to explore how biography and techniques helped the artist to never put down roots in a place alone.

Q: How would you describe Doig’s painting to a new viewer?

One of the great strengths of the way that Doig paints, and the way that we respond to his paintings, is that they both feel very vivid and immediate. You are immersed in that painterly world that he creates. But at the same time, as you’re feeling very vivid, there is also this sense of distance and slight dislocation.

Q: Dislocation is a chronic element in Peter Doig that affects both his life and, consequently, the approaches taken in his artistic production more practically. Where does it stem from?

I think it has to do with the fact that he often paints from memory or from a photograph that provokes a memory. That lived experience somehow feeds into the such authentic way he paints, which is based on the collaging of memories, of found images, of the different forms that music often takes on and the way it appropriates different styles. In so doing, his lived experience and his creative experience come together through paintings.

Q: What does this suggest about the way he relates to the environment through his paintings?

There is nothing contrived about what he does. Doig never makes the mistake of thinking he is ever fully rooted or embodied anywhere that he is, of feeling like he is totally embedded. Of Trinidad, he absolutely loves and embraces the culture, the people, the music, but he always feels slightly outside of the place. He’s always one step removed.

Q: In works like ‘Alice at Boscoe’s’, where Doig portrays his daughter in a hammock in the garden of a family house he rented in Trinidad, the way he plays with paint and charcoal, as well as with linen, is also quite emblematic. Don’t you think it further reiterates the message of dislocation?

You are right. It’s interesting to see how he handles paint and the effect it has on our perception of the paintings and our experience of them. He’s found ways of painting in the way that we remember or half remember things: he feels very akin to trying to call up an image in your mind which is vivid in places and, all of a sudden, fades away. The various textures and thicknesses of paint that he uses, the way that they often bleed into one another, the colours and the forms, speak to and convey that very strongly.

Q: This is in a quite stark divergence from the rigidity of grids he employs in ‘Music Shop’ or ‘Night Studio’ to delineate and delimit the ambience outside. Do you see any metaphoric reading for that?

Yes, in those pictures that you mentioned, those grids are actually based on real window grills and door grills that he observed and painted from life. For instance, the music shop is actually based really closely on an actual shop in Port of Spain and, like quite a lot of the buildings in Trinidad, it has security grills on the window.

However, I think grids do have a symbolic quality very clearly. In ‘Music Shop’, they depict the theme of freedom versus incarceration, and the sense of shadows trying to walk through different spaces. Whereas, in ‘Night Studio’, they contribute to the moonlit atmospheres of the picture by contrasting complex planes and patterns.

Q: Speaking of which, the night seems to have a decisive role in Peter Doig’s art both at a creative and functional level. I noticed it as a common setting for several of the paintings displayed in the first part of the show.

Yes, we made a feature of night in our first room by having a series of nocturnes. It is really telling that Doig can only really get into the zone of painting during the night. He has talked in the past about liking to work when everyone else is dreaming. Things as we know do look strange, and the world does become a different, unsettling, more mysterious place of possibility and danger at night. He really pays off that quite a lot of his nocturnal works.

So, I believe that his paintings’ dreamlike quality that you sometimes feel in his oeuvre relates to that.

Q: As you said, night also conceals what we are not used to. Is this peculiar fascination for strangeness that endows many of his works with an eerie, weird patina?

Making the familiar strange is something that does reoccur in his work and, to a degree, as a sort of hallmark of his art. He is brilliant at bringing moments which you don’t quite know the context about into his painting, or at creating paintings that express those moments. You keep wondering where that sense of mystery is going to take you.

Q: Take the musicians replacing fishermen in ‘House of Music (Soca Boat)’: Doesn’t this atypical, almost surreal choice in representing subjects and their context add to his intention to make the familiar strange?

I agree, even though it is a homage to the backing band of Calypso music or Trinidadian swing music, those players do become anonymous unless you’re really knowledgeable about them. He leaves them only lightly finished; they appear like a fading memory in some regard that he brought out in that eerie way.

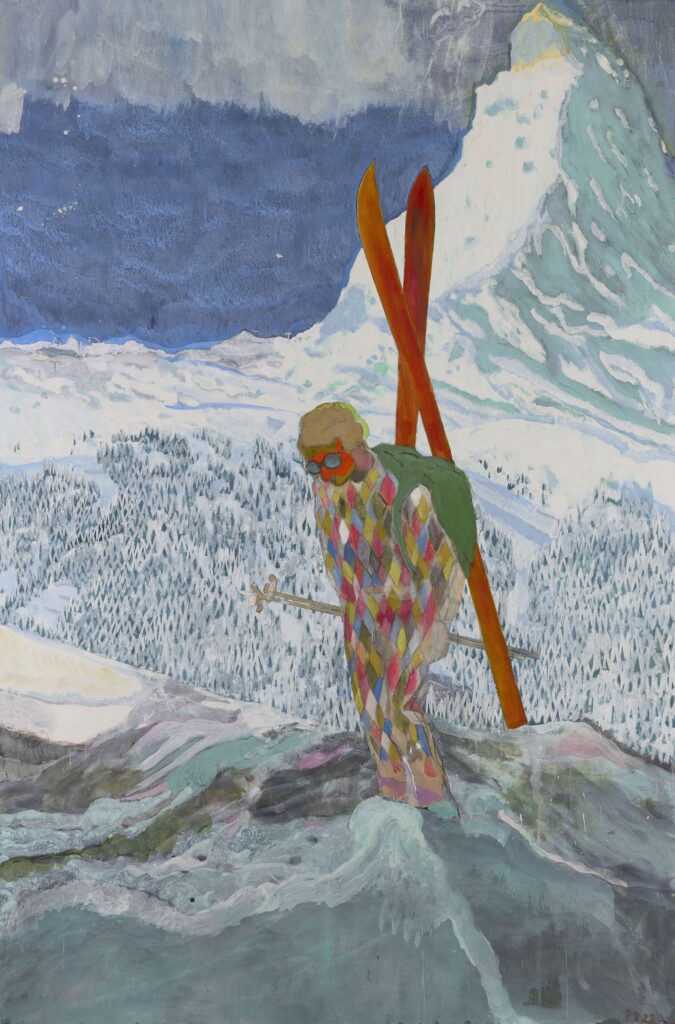

Q: Something analogous happens in ‘Alpinist’, right? As a viewer, I was astonished by the Alps and could almost feel the burden put onto the subject by the crossed skis on his back, which have a religious connotation, and by nature behind.

Yes, when you look at it, it’s almost vertiginous. It induces a state of anxiety in front of the magnificence of nature that the scale of the painting also helps create. Doig has managed to create a brilliant depth that engages with the big idea of the sublime, epic landscape that overwhelms the subject, who is genuinely awed by nature.

Q: And then the skier is dressed with a harlequin costume.

Anecdotally, that picture goes right back into a romantic tradition, where Doig puts the subject in a harlequin costume as a sort of alter ego for an artist. I think he sees the artist’s creative journey as being one that is also quite daunting, intimidating and constantly hinged on nature, making them aware of their own relative insignificance.

Q: It is the first time that The Courtauld hosts the exhibition of a contemporary artist after it reopened in November 2021. How did curating a show on a living painter differ from presenting a retrospective? To what extent did Doig participate?

In working with Peter Doig, one of the first things we did was to show him and talk about the spaces. He thought very carefully about what works he was going to make for the exhibition, their scale and impact in relation to the room. I think with artists like Peter Doig, if you look back at his exhibition history, it’s tended to be really quite big survey shows of much of his career. Instead, what we wanted to do or thought that we could offer here was a smaller, more focused look at this recent body of works. You do get that sense of being in his studio and see the pictures that he made together in a room of a similar scale.

Q: How can you manage to keep the message big, truly enabling the exploration of an artist and their work, in the limited space Denise Coates Exhibition Galleries that is allocated to temporary exhibitions?

We very much design our exhibitions with that specific space and scale in mind. Over the years, we have wanted to make types of exhibitions that you perhaps don’t see elsewhere in London. This approach offers something different; it encourages people to slow down, to spend more time with fewer works, and to get rather deeply engaged with a hopefully very exciting or interesting episode from art history or aspect of an artist’s work. Moreover, the idea of looking more closely at and putting out more research and insight also feels quite appropriate as The Courtauld is a university art gallery.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

*

The Morgan Stanley Exhibition: Peter Doig is sponsored by Morgan Stanley and supported by Kenneth C. Griffin and the Huo Family Foundation, with additional support from the Art Mentor Foundation Lucerne.