At tablecloth, we’re all about the ways we can come together over food. But what about those times where religion imposes restrictions on how and what we eat. On the eve of Ramadan, a festival during which food and drink are restricted, we asked people who fast how it affects their lives

With spring fast approaching, many people are taking the time to prepare themselves to observe a variety of different religious holidays and festivals. This notably includes the holy month of Ramadan, celebrated by Muslims – but the concept and act of fasting is not unique to Islam, with Jews who observe Yom Kippur in the autumn and their diets change in religious observance, as well as Christians, beginning Lent in February for 40 days, and Buddhists who frequently fast on new moon days.

Different religions have their own meaning as to what fasting is and means to them. Why would anyone voluntarily give anything up, especially something as essential to life as food? Don’t they feel hungry? Why would they do that to themselves? Well, everyone has a different take. Here’s just a few.

Leems, 24 from London is Muslim and, during the month of Ramadan, restricts their food and drink from dawn-till-dusk.

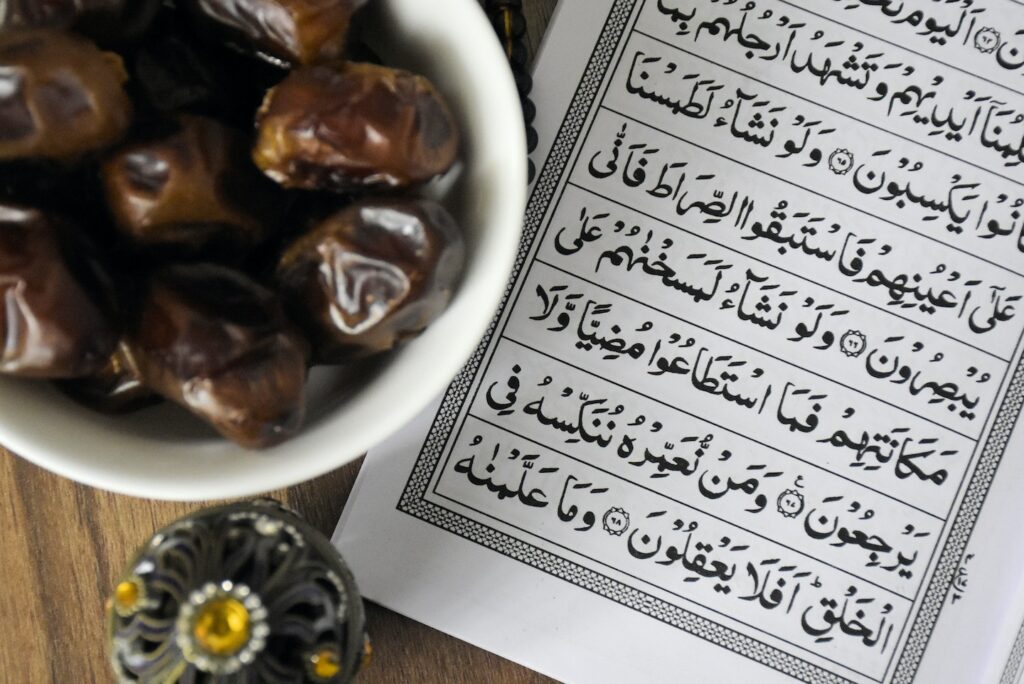

In the early hours of the morning when all is quiet and the rest of the world is still fast asleep, I’m sat at my kitchen island with a date – the fruit, not a person – a bowl of porridge a glass of water and a sense of calm surrounding me. There is nothing like the last sip of water before Suhoor ends which is the meal before the sun is about to rise. It’s the first sign that the day is about to begin along with my fast.

That last sip of water quenches a thirst that’s so deep within you both physically and spiritually, which is absurd because the water I drink is nothing special. It’s the same water from the same tap I have been drinking from for the last twenty years. But when the holy month of Ramadan is upon us, it allows me to stop and really appreciate the simple things in my life, like a glass of clean drinking water. A glass of water has no real taste; water is water. But there is something about knowing I won’t be able to have any more until sunset that changes the taste and the meaning behind it.

The Holy Month of Ramadan is the ninth month in the Islamic calendar and is different to the recognised Gregorian solar calendar I use every day. The dates that I, along with all my other fellow Muslims, fast on change every year due to the Islamic calendar being based on the cycle of the moon. This means the sighting of a new moon marks the beginning of the month which can be both exciting and challenging. As I live in the city and can’t see a thing due to the smog and clouds in the air, it makes it hard to see the moon. But the instant the moon is spotted, the celebration and excitement fill the air and I receive a flood of messages from family and friends wishing me a happy Ramadan.

The month of Ramadan itself holds huge significance to me personally, but also to Muslims across the globe. I have fond memories of waking up early in the morning to have Suhoor with my family and waiting to be old enough to fast with them. I would relentlessly ask my mum if I could fast until the age of 12 when I was able to partake in my first ever fast and it’s a memory I will never forget.

Fasting, also known as Sawn, is one of the five pillars of Islam which all Muslims must adhere to be a member of the faith. This means fasting is obligatory for all who are able to. The other pillars are Shahada, a declaration of faith; Salah, meaning prayer; Zakat, the donation of wealth to charity; and Hajj which is pilgrimage.

I break my fast at dusk with a date and a glass of water at Iftar, which is the meal I share with my loved ones and eat different kinds of food every day. One of my favourites is Kajari, a flavourful rice soup with Dal fritters. The concept of fasting in Islam goes beyond not just being able to eat or drink anything including water during Ramadan.

I use the month to reset and spend time on myself to reflect on my life spiritually and develop and strengthen my relationship with my creator Allah SWT, Subhanahu wa ta’ala which means ‘the most glorified’. I achieve this by praying five times a day, asking for forgiveness, and reading the Quran to increase my knowledge of Islam. I also try to perform good deeds like volunteering at my local Islamic charity and spending time with community, family and friends at the mosque which all help me create good habits that I can continue even after Ramadan is over. The month also opens my eyes to how lucky I am and makes me feel very grateful for all the little things I take for granted like clean water, food and shelter.

Jackie, 25 from North-west London is Jewish and fasts six times a year. Her most recent happened during the festival of Yom Kippur.

My last full meal was the seudah ha-mafaseket where traditionally I eat a piece of bread and a boiled egg on the eve before Yom Kippur which lasts 25 hours. Since my bat mitzvah, a coming-of-age celebration at the age of 13, I was taught that fasting opens up a spiritual awareness. I had to be a physical key in the form of fasting to be able to unlock and connect with God, without any worldly distractions to divert my attention.

The festival lasts from one sunset to another and is the holiest day in the Jewish calendar. There are 6 main fasts throughout the Jewish year. Two are major fasts which last from one evening to another, whilst the other four are minor fasts which begin at sunset and end at nightfall. The latter are my personal favourites.

Yom Kippur is also known as the day of Atonement and is celebrated ten days after Rosh Hashanah the Jewish new year. Jewish take the day off and are exempt from day-to-day tasks and distractions such as work and cooking. We also try to abstain from earthly pleasures such as bathing, wearing leather shoes to using technology, as they are seen as luxuries. Although Yom Kippur is a special holiday, it is notably difficult and requires prior preparation both spiritually and physically. It can take a toll on my physical body, as no food or drink can pass through my lips until the next evening, which I share with my loved one.

The Torah, which is the religious scripture Jewish believers follow, states that fasting on Yom Kippur should be practiced by those who are able to repent for past sins is the practice of self-denial which is achieved by fasting. I chose not to eat during Yom Kippur and wear white clothes to symbolise purity and renewal as I repent for my past transgressions and feel a stronger connection with God on that holy day. Most of the day is spent at the synagogue praying with family and friends.

The rest of the time I preserve my energy and reflect on my own. When I am alone, I can sort through my thoughts and feelings without distraction until it’s time to break my fast in the evening. The holiday is tough but and serves as a reminder that a new year has begun and I can learn from my past to better my future.

Martha, 26, from Luton practices intermittent fasting as part of her religion Buddhism with movement as an added restriction

As the sun begins to set, an hour can sometimes feel like only a handful of minutes when I am in a state of reflection and calm during my meditation. Being sat in the same position with my legs cross and hands clasped together in my lap always takes me back to almost six years ago when I began my Buddhism journey. I was accepted into the religion with a ceremony known as ‘taking refuge in the Triple Gembut’, following the teachings of a man called Siddhattha Gotama who was also known as the Buddha, whom is awakened.

Buddhism believes in four core Noble Truths and the Eightfold Path. These truths are at the heart of the religion and are related to different forms of suffering: The truth of suffering, The Cause of Suffering, The End of Suffering, and what Leads to the End of the Suffering. By following the four noble truths and the eightfold path, believers can achieve a state called nirvana, which can end in the continual rebirth and discomfort that comes with reincarnation.

Another core practice I was taught is self-control which can be demonstrated by fasting. When I began learning about the faith, it urged monks and followers to not consume any solid food from the afternoon. On full moon days, those who also follow the eight Precepts of Buddhism also fast; these are eight acts of abstinence and one act states to abstain from eating anything substantial after noon in order to practise self-control. Fasting or forgoing a meal, once a day or for how long I desire, is intended to help those less fortunate who are hungry or do not have a proper meal every day.

This fast is also known as intermittent fasting which I try to include into my routine to keep up with my faith but can be difficult to practise regularly with the pressures of everyday life. However, unlike other religions, fasting is not required for Buddhists since it also includes restricting movement of the mind, speech and body, as well as restricting food and drink. This is where meditation comes in: it helps practise self-control and results in a successful and unbelievable level of spirituality.

Cathy 30 from Ireland observes the 40-day fast of Lent every year as part of her catholic faith.

At the start of the season when the flowers begin to bloom and the weather turns slightly warmer, I know that my 40-day countdown is about to begin. I grew up in a catholic church which was like my second home. My mother would dress me in my best clothes, and we would make our way hand in hand to the church to help with the preparation leading up to the big day.

I would always volunteer to help set up the candles and watch as, one by one, people would light them and say a prayer ahead of the holiday. The sight of the burning candles and bright decorations creates an indescribable atmosphere, as if the holy spirit was around me, which fills me with a renewed sense of faith.

The forty days known as Lent lead up to Easter, the holiest day in the Christian calendar which commemorates the resurrection of Jesus Christ and celebrates his victory over sin and death.

During Lent, I and many other Catholics practice forms of self-discipline as penance. On Ash Wednesday, the first day of Lent, and Good Friday, the last Friday before Easter, I fast and abstain from eating meat as in the bible it was considered a luxury.

Both the Old and New Testaments support the biblical discipline of fasting. Christ wanted his disciples to fast, which is why in the bible there is guidelines on how to accomplish it. In Christianity, the number forty is special as it is the traditional number of judgement and spiritual trial found in the Bible. For this reason, Lent is traditionally forty days long though it lasts 46 if you count the Sundays. It is also the same number of days of fasting Christ undertook in the desert before beginning his public ministry.

Over the years I have chosen to abstain from other pleasures during Lent such as coffee, alcohol and technology. But the hardest thing I chose to abstain from was chocolate which made me conscious of my modern comforts and allowed me to reflect on my life, that is the actual intention of the fast. I also use the time to reflect on my life and look at things I can change, whilst being very grateful for all I have.

If you want to find out more about Ramadan :

All images, Ⓒ pexels and unsplash.