Food production and hospitality sectors are dominated by precariously employed migrant workers, who once seemed to be outside of the reach of large trade unions. Now, they are leading the movement.

“When I moved here, I didn’t know anything about trade unions,” says Justyna Kamienska, a representative of GMB, one of the largest trade unions in the UK. She moved to Yorkshire from Poland in November 2014, and although she quickly found work in a bread factory through an agency, she soon realised that she was routinely shortchanged out of her wages. “I would not be paid for my holidays, I would not be paid for all my hours,” she said. “I mentioned it to a friend at work and she told me, ‘join a union they will help you out.’”

By June, Kamienska was a proud union member, and today she is the leader of the only migrant-specific union branch in the UK. However, among migrant workers who are over-represented in the low-paying food and hospitality industries and most likely to experience workplace discrimination and exploitation, Kamienska is very much an outlier.

“Workers from the A8 area [countries which joined the EU in 2004] just aren’t unionised,” says Dr. Roch Dunin-Wąsowicz, a researcher at the London School of Economics. According to Dunin-Wąsowicz, Eastern European migrants are faced with a “double-whammy” when it comes to unionising: on the one hand they tend to be culturally averse to trade unions, on the other they are most likely to be precariously employed and work in sectors with little union presence, such as hospitality and agriculture.

“Among Poles, for example, there is scepticism towards unions because of what what happened to trade unionism [in Poland] after 1989 and how politicised it became,” Dunin-Wąsowicz explains. “In Poland one does not belong to a party, one does not belong to an association.” Additionally, low-paid migrant workers often find the membership fees off-putting.

“When I am trying to recruit new members,” says Kamienska, “I do encounter a lot of reluctance. People say, ‘but you didn’t help my friend,’ ‘but you only want my money,’ etc. People just don’t understand that unions here are not the same as in Poland.”

‘They didn’t show any care for us or any interest, they said they would call us back, but they never did. I think that tells you everything you need to know’

According to Dunin-Wąsowicz, the prime motivating factor for those migrants who do join a union are workplace disputes. “The migrant union members in our study said they learned the value of trade unionism because they were confronted with injustices in the workplace, this is especially true of women,” he says. “One female union member worked in a poultry processing plant. She started a protest against sharing wellies with other staff members and then organised strike action. Now she’s a union rep.”

However, even once migrant workers find their way to a union, they are often faced with barriers. Jésus Jiménez worked as an office-worker in Madrid for fifteen years before he decided to move to London. He was hoping to learn English and change his environment. As his language skills were poor at the time he took on an agency cleaning job at a city-centre private-member’s dining club. Instead of a learning opportunity however, he was quickly confronted with a culture of humiliation and abuse. “Sometimes managers would make advances towards female staff members,” Jiménez said through a translator, “and if they were rejected they would penalise them by decreasing the amount of hours they could work and cutting their pay.” The managers employed similar tactics against employees who protested against excessive workloads.

Jiménez, who had been a union member throughout his working life in Spain, had none of the Eastern European reservations towards trade unionism. His first instinct was to google search for an appropriate organisation to join, which is how he came across Unite, one of the largest British unions which covers hospitality workers. However, he was soon disappointed.

‘Ideologically, trade unionism is a movement that defies national boundaries, and rightly so, but that can also hamper their understanding of the experiences of migrant workers‘

“They didn’t show any care for us or any interest,” says Jiménez, “they said they would call us back, but they never did. I think that tells you everything you need to know.” Additionally it was difficult for Jiménez to persuade his colleagues to join him in unionising. Many were reluctant to do so due to the language barrier as well as the cost of membership. “At the time the membership was about £15,” he says. “which is quite a lot for a low-earning worker.”

Jiménez’s experience shows how lucky Kamienska was to find a union branch which was run specifically for and by migrants. GMB’s Yorkshire and North Derbyshire migrant branch is the only such branch in the UK.

“Ideologically, trade unionism is a movement that defies national boundaries, and rightly so,” says Dunin-Wąsowicz, “but that can also hamper their understanding of the experiences of migrant workers.”

“They do not see nationality, they don’t want to differentiate members on that basis,” he explains. “So while they might provide language and translation services, they do not cater specifically to those populations; they don’t provide opportunities, or access points that will be specifically designated for migrant workers.”

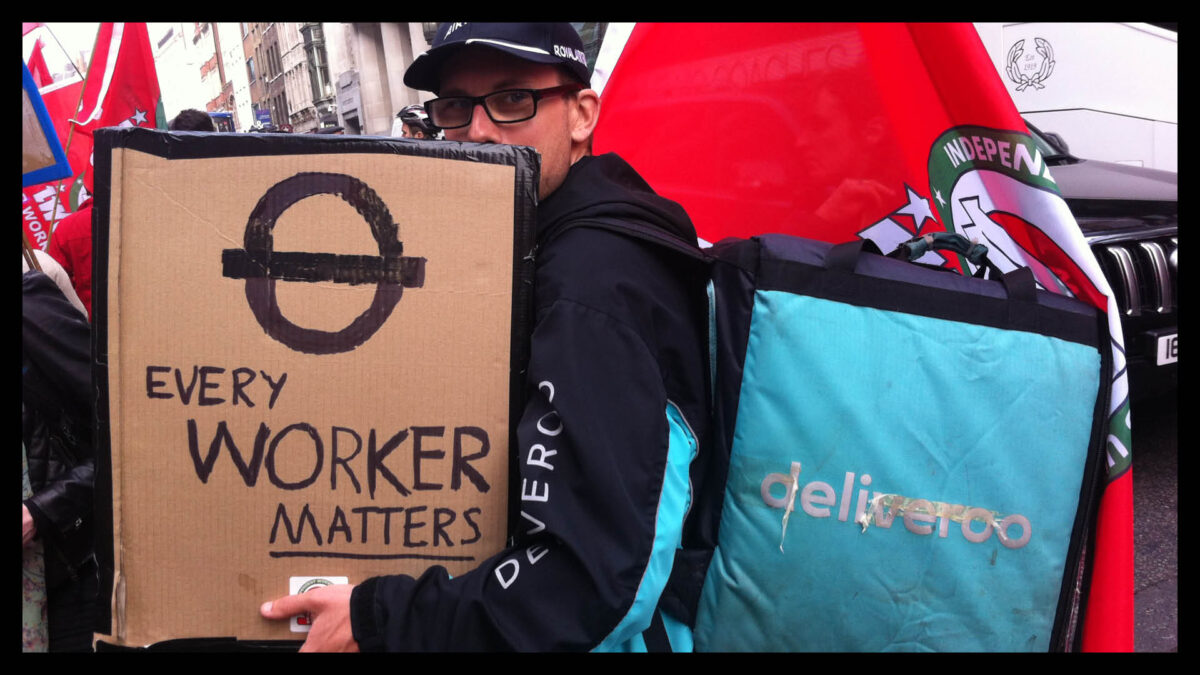

Henry Chango Lopez moved to the UK from Ecuador twenty years ago and found employment through various agencies as a cleaner at University of London (UoL). Last November he was elected as the chairman of Independent Workers of Great Britain, a small grassroots trade union which managed to unionise the workers in the sector which has traditionally been seen as the hardest organise: the gig economy.

Chango Lopez, like Jiménez who now is also an IWGB member, initially sought help from a large and established trade union, Unison, which had the recognition of his employer. However, he too grew disappointed as the branch proved ill-equipped to accommodate the majority Spanish-speaking workers.

“At the time there was a lot of Latin American workers who spoke Spanish,” says Chango Lopez, “so we asked the branch to hire an organiser who was bilingual. But what we heard next, was that they hired a white British guy who did not speak Spanish.” The English-speaking organiser, Chango Lopez explains, would instead invite the management to translate during his meetings with the workers. “Obviously nobody wanted to talk about any issues [at the workplace] with their manager translating,” he said.

However, Chango Lopez, unlike Dunin-Wąsowicz, did not point to the unions’ ideological nationality-blindness as the reason for their short-comings in accommodating migrant workers. Instead, he says, the rife exploitation which precariously employed workers face is too big a challenge for established unions. “Not everybody who works in these industries [catering, hospitality] is a migrant, there are many other people working there too,” he says, “unions just are not prepared to help, it’s just too much work for them.”

For Rosa Crawford, a spokesperson for Trade Union Congress, a federation of trade unions in England in Wales with which IWGB is not affiliated, unionising migrant workers should be a more grassroots process. “It’s an organic process that where migrants are most likely to be in certain sectors, the branches are most likely to have more migrant workers,” Crawford explains, “and often the activists are most likely to be migrant workers, because they’re the ones being treated worse and are the ones that come forward.”

Crawford also pointed to the changes within the trade union culture over the last twenty years, especially following the “sudden expansion of the labour market” in 2004 when A8 countries joined the EU. “Equality agenda has become a more important issue,” she said, “and I think a recognition of how much migrants are likely to be in the most exploited forms of employment.”

“I think, I just want people to join a union,” said Kamienska. Today, seven years after moving to Britain, she is not only a factory worker, but a union rep and a self-described activist. She says that she often gets emails from Polish workers all over the UK, but she cannot help them if they’re outside of her branch’s jurisdiction, unless she has the local rep’s permission. That being said, Kamienska is quick to add that she is often contacted by GMB reps all over asking for her help and advice.

“We just need more migrants to sign up,” she says, “because, you know, there is strength in numbers.”